Thematic report by All Survivors Project and London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

Acronyms

AoR – Area of Responsibility

ASP – All Survivors Project

BID – Best Interest Determination

CAAFAG – Children Associated with Armed Forces and Armed Groups

CAR – Central African Republic

CMR – Clinical Management of Rape

CRSV – Conflict-related sexual violence

CP – Child Protection

DRC – Democratic Republic of Congo

GBV – Gender-based Violence

GBVIMS – Gender-based Violence Information Management System

HCT – Humanitarian Country Team

IDP – Internally Displaced Persons

IRC – International Rescue Committee

IPV – Intimate Partner Violence

LGBT+ – Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and other gender-non-conforming individuals

LSHTM – London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

MENA – Middle East and North Africa

MHPSS – Mental health and psychosocial support

MSF – Médecins sans Frontières

MSM – Men Who Have Sex with Men

NGO – Non-Governmental organisation

NRC – Norwegian Refugee Council

SEA – Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

SGBV – Sexual and Gender-based Violence

SRH – Sexual and Reproductive Health

SDC – Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation

STI – Sexually transmitted infections

SV -Sexual Violence

ToR – Terms of Reference

WHO – World Health Organisation

YHDO – Youth Health and Development Organisation

Introduction

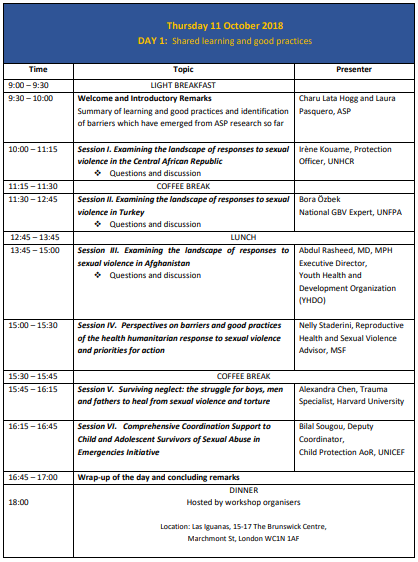

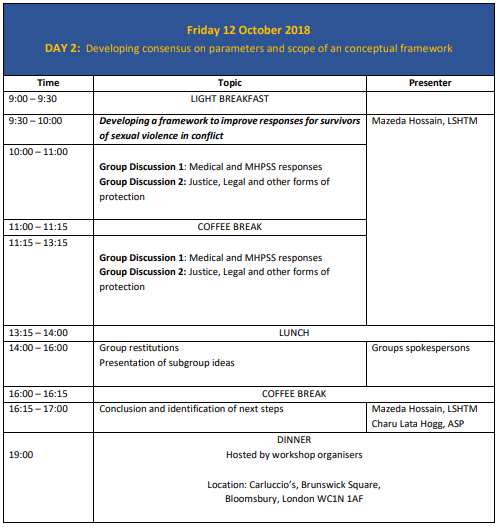

This report presents a summary of discussions conducted during an international workshop “Building knowledge to improve existing service responses for all survivors – Developing a conceptual framework outlining the links between conflict-related sexual violence against men and boys, health sector and policy responses for conflict-affected populations” held in London, UK, on 11-12 October 2018 and co-organised by All Survivors Project (ASP) and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM).

The workshop brought together humanitarian and human rights practitioners, academics, experts and donors to understand responses for male survivors of sexual violence in conflict and displacement settings. Led by ASP and LSHTM, the initiative was conceived as the first step in a multi-staged process which aims to develop a conceptual framework on responses for male survivors in conflict and displacement settings. This framework will help build on global and national sectoral guidelines and response frameworks to ensure that all survivors of sexual violence have access to appropriate, inclusive and competent response services.

This document has been prepared and finalised by All Survivors Project staff following review by LSHTM and workshop participants. The workshop agenda is available in Annex I and the list of participants is available in Annex II.

Workshop background and objectives

All Survivors Project’s research in Sri Lanka, Bosnia & Herzegovina, CAR and Syria/Turkey shows that men and boys and gender minorities are still largely left out of the response mechanisms including in services providing medical, mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) and legal response services, even when these services are developed and designed to respond to sexual violence and gender-based violence (GBV) against all survivors. While the reasons for this are several and diverse, ASP findings so far suggest that some key reasons might include the lack of in-depth global evidence-based knowledge and guidance on what constitutes a comprehensive, accessible and competent sexual violence response for male survivors and other gender minorities, and the consequent lack of knowledge and awareness of providers on how to provide care for male survivors.

ASP and LSHTM brought together key practitioners and experts to discuss this issue with the aim of achieving the following key objectives:

- Share research findings, including good practices and a clearer identification of barriers that have emerged from the research on male survivors of sexual violence conducted by ASP so far in different contexts;

- Examine the available responses for survivors of sexual violence in Central African Republic (CAR), Turkey and Afghanistan and deepening understanding of the barriers and good practices for men and boys in each context;

- Develop a consensus on parameters and scope of the conceptual framework.

A portion of the workshop was devoted to group discussions, with the aim of encouraging participation, knowledge and experience-sharing by participants in their respective areas of expertise.

Participants

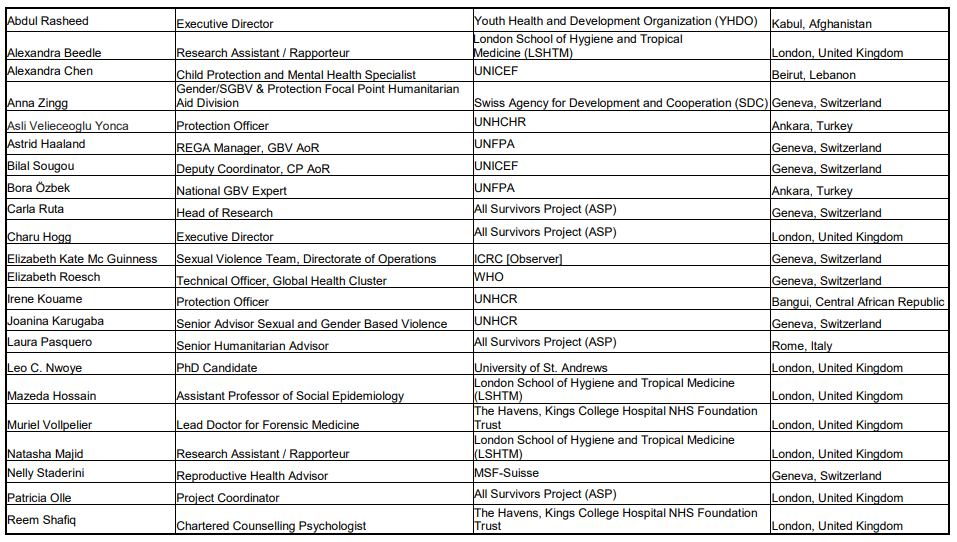

A total of 22 participants attended the two-day workshop. These consisted of representatives from Interagency mechanisms, UN agencies, international and national non-governmental organisations (NGOs), the academia and donor agencies. A list of attendees is provided in Annex 1.

Day 1 – Thursday 11 October

Welcome and Introductory Remarks

Summary of learning and good practices and barriers which have emerged from ASP research so far

Ms. Charu Lata Hogg, Executive Director, All Survivors Project

Ms. Laura Pasquero, Senior Humanitarian Advisor, All Survivors Project

Ms. Hogg welcomed participants and provided a brief overview of the history and mission of All Survivors Project. Since it came into being in December 2016, ASP has focused on sexual violence against men and boys in conflict and displacement settings, a field about which little information is being collected, analysed or shared at the national and the global level. As ASP conducted research on specific country contexts, from Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Central African Republic (CAR) and Syria and Turkey, the organisation realised that there was an urgent need to understand and analyse humanitarian responses available for men and boys in various contexts and the actual access that men and boys had to these responses. ASP findings showed that a series of important gaps exist in all contexts. ASP’s future work is based on a premise that a policy shift needs to happen: while responses for women and girls need further strengthening and funding, there is a need ensure that responses include all survivors regardless of their gender, race or background.

ASP’s work is structured around the two ‘pillars’ of understanding and strengthening human rights and accountability on one side, and on humanitarian responses on the other. It is in pursuit of the second core aspect of its work that ASP is building consensus with its national partners in CAR, Turkey and Afghanistan on the need to ensure that men and boys are taken into account by humanitarian actors that provide responses to sexual violence. ASP aims to use the consensus, collectively generated knowledge and learning from national partners to inform global policy and guidance by deepening its understanding and acceptance within this group.

ASP Senior Humanitarian Advisor Ms. Pasquero summarised ASP’s findings and learning on the issue of humanitarian responses to men and boys and explained how ASP research so far shows that men and boys are still largely left out of response mechanisms and are absent in response services. While the reasons for this situation are multiple and there is some commonality with women and girls, such as the lack of response services to sexual violence in some settings, a wide range of other barriers seem to be specific or higher for men and boy survivors. These include, for example, the barriers to disclosure that are linked to victimblaming and re-victimising societal attitudes towards male survivors, which compound the difficulty for male survivors to come forward. Many male-specific barriers appear internal i.e. linked to elements that depend from the action or inaction of the organisation or service providers, for example the lack of expertise and capacity of service providers to identify and provide support to male survivors, the lack of sufficient entry points into services that are suitable for men and boys, or the lack of clarity on sectoral and institutional responsibility for sexual violence against men and boys at the coordination/cluster level. When considered in entirety, these elements combine to create an impression of a response system that, although inclusive of male survivors in principle, seems de facto mainly focusing on women and girls.

Ms Pasquero summarised practices that have emerged, in ASP research in focus countries, as being successful in the identification of, and response towards men and boys. Some of these practices include, carrying out community awareness and sensitisation programmes about male sexual violence in the community and in schools, or working with services and mechanisms that are able to identify male survivors and refer them for services, such as listening centres or child protection projects. Working with community leaders in an attempt to shift community attitudes and perceptions about male victimhood and counter the isolation and rejection experienced by male survivors has also emerged as a good practice in CAR. The research in Turkey showed that training health professionals in clinical management of rape (CMR) including for male survivors and working with specialised organisations such as LGBT+ organisations increases the likelihood that services identify male survivors. Participants engaged in a lively discussion on the appropriateness and risks of doorto-door services and home visits, which have worked in some displacement settings in opening doors to services for men and boys, but considered by some participants to be potentially stigmatising (e.g. to family members or the community) if these visits have the specific purpose of identifying survivors and without careful training of providers.

Finally, Ms Pasquero highlighted that, while working with the ultimate goal of achieving better access for all survivors to quality, survivor-centred and multidisciplinary support, ASP’s work has managed so far to catalyse interest and build consensus within focus countries on the need to create better responses mechanisms that are inclusive of men and boys, and on the need to work across all sectors. In the framework of the new partnership, LSHTM and ASP aim at developing a new conceptual framework and multi-country set of evidence, on improving access to health and well-being for male survivors of SV. The framework will, in the long-term, help develop global and national sectoral guidance to ensure that all survivors of sexual violence have access to appropriate, inclusive and competent response services.

This two-day workshop intends to lay the groundwork for a general understanding of the overall sexual violence response landscape in the three different contexts where the multi-country study will be conducted – CAR, Turkey, and Afghanistan – and examine good practice being developed by humanitarian experts and organisations in the health, MHPSS and child protection sectors. The second day centred on group discussions on what issues (e.g. patterns, indicators, barriers and needs)should, ideally, be considered that appropriately addresses the needs of male survivors of sexual violence. Participants were encouraged to share experiences from their countries and in their field.

Six months after the first inter-agency workshop on responses to men and boys in Bangui, CAR, held in April 2018 and co-organised by UNHCR and ASP, this workshop in London with experts from a variety of fields and countries has been identified as a pivotal step in helping start this crucial knowledge-generating process.

Session I. Examining the landscape of responses to sexual violence in the Central African Republic

Ms. Irène Kouame, Protection officer, UNHCR Bangui

Ms Kouame provided a general overview of sexual violence response mechanisms in the first of the three focus countries, the Central African Republic (CAR). She gave a brief background of the types of SGBV survivors in CAR (e.g. refugees, IDP) – explaining that their response focuses on all survivors (and not exclusively on any particular sex or group). She highlighted that some causes or drivers of SGBV in CAR include social and gender inequalities (particularly in terms of the distribution of power relations and social status) between men and women. She said that GBV presently endures in CAR because of sustained (and ongoing) civil armed conflict since 2012, low education levels, deep poverty, economic dependence on external suppliers, harmful traditional practices, weak institutions and a culture of impunity and silence.

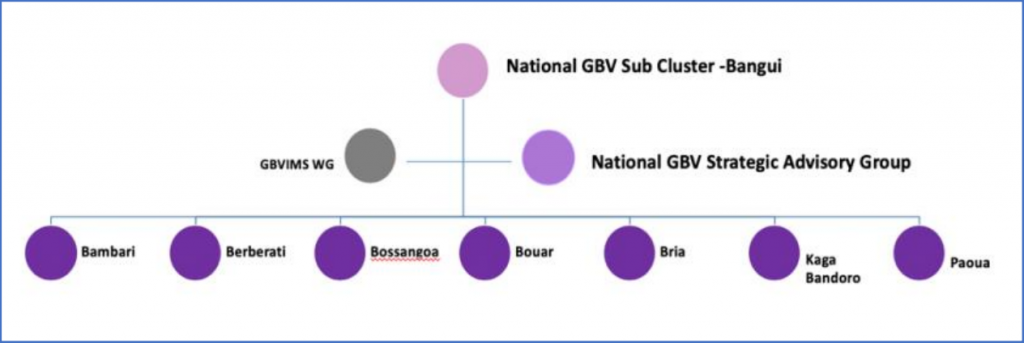

Sexual violence response coordination in CAR is structured within a national GBV sub-cluster and regionallevel GBV sub-cluster in seven of the sixteen regions in the country (see image below), supported by an interagency national GBV strategic advisory group, in charge of supporting strategy development. The mainstream response available for survivors in CAR (primarily in the capital, Bangui) is comprehensive of medical assistance, including CMR, pregnancy management and support or referral for complementary care; psychosocial support provided in listening centres and including counselling, mediation, and provision of dignity kits as needed; legal assistance and legal accompaniment; and socio-economic reinsertion including livelihood activities for most vulnerable survivors. As regards socio-economic reinsertion, Ms. Kouame observed that while it was only provided by the partners of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in their activities, men and boys never seem to request for this form of assistance.

In a context that remains highly unsafe and insecure and sees a shortage of funding, Ms. Kouame highlighted the high humanitarian needs and considerable gaps in the SV response especially in some regions of CAR, particularly in Eastern regions like Bangassou, where few humanitarian organisations are present as access remains challenging. There were also gaps in resources and in meeting all survivors’ needs. The main gaps highlighted in the SV response include inadequate psychological assistance for survivors: there are a limited number of psychologists present and no clinical psychology training programmes in the country. In addition, access to protection and justice response is available exclusively in Bangui and capacity and training of justice actors on how to deal with male survivors remains low. Ms. Kouame pointed out that gaps in responses and barriers seem higher for male survivors who are largely absent from response services. Barriers to providing appropriate responses included limited staff skills and knowledge on male sexual violence. A lower use of services by men and boys may also be attributable to the lack of male focused prevention and response messaging and services. The majority of sexual violence prevention and response services are targeted at women and girls. Ms. Kouame also highlighted that the legislative framework around sexual violence is silent on men and boys, as either neutral, like the Penal code, or focuses exclusively on women and girls as demonstrated by a number of specific laws.[1]

Ms. Kouame illustrated some positive results and good practices. Although still largely under-reported, the country Gender Based Violence Information Management System (GBVIMS) shows that 10% of the overall GBV incidents registered in 2017 (11,110) concern male survivors[2]; although it is impossible to isolate incidents of sexual violence from the overall GBV, this data shows a certain level of reporting by this group.

Medical and psychosocial care is currently provided by Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) in Bangui who identify and treat a number of male survivors. Defined as “good partners” by Ms. Kouame, MSF in Bangui has also supported ASP work in the country. In addition, the Joint Rapid Response and Prevention Unit for Sexual Violence against Women and Children (UMIRR), a specialised police unit set up to investigate crimes of sexual violence, was also highlighted as a positive development. Although in need of further training on how to respond and provide certain services (like safe houses) to male survivors, UMIRR represents opportunities for building in a response to sexual violence against males as part of its broader work. Finally, some targeted actions and disseminated knowledge/information for specific groups, like child survivors, children associated with armed forces and armed groups (CAFAAG) and survivors in detention situation has so far been genderinclusive, targeting both male and females, boys and girls.

Ms. Kouame stressed the need for more sensitisation, and the need to build on positive developments while trying to address gaps and highlighted opportunities that CAR offers to include a stronger focus on men and boys in the development of the National GBV strategy (2018-2021), in the GBV Sub-cluster approved work plan 2018 and in the Humanitarian Country Team Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (HCT SEA) approved work plan for the period 2018-2019.

Session II. Examining the landscape of responses to sexual violence in Turkey

Mr. Bora Özbek, National GBV Expert, UNFPA

Ms. Asli Velieceoğlu Yonca, Protection Officer, UNHCR

Mr. Özbek presented an overview of the sexual violence response system in Turkey, a country that hosts the largest population of refugees in the world i.e. 4 million refugees, with a current increase registered in the number of Syrian men and boys (21% are men and 24% are boys in 2018). He contrasted these figures with non-Syrian refugees also in Turkey – of which 46% are men and 17% are boys. Most Syrian refugees live in temporary accommodation facilities in urban areas and a minority are based in camps.

Mr. Özbek emphasised that the available data shows that gender-based violence, including sexual violence, is experienced by all genders and all ages among the refugee population, with domestic violence, rape, child abuse, survival sex including amongst LGBT+ individuals, being the most common forms, suffered mainly in the country of origin but also in Turkey. In Turkey, boys are reported to being exposed to sexual harassment from landlords, taxi drivers, neighbours, relatives and acquaintances. He explained that typical roots causes of GBV that affect host communities include gender inequality, discrimination and abuse of power. Additionally, several contributing factors increase the likelihood of GBV occurrence within the refugee communities in Turkey – these include cultural and socio-economic dynamics, barriers against social inclusion and discrimination.

In the absence of the standardised data collection using the GBVIMS in Turkey and with a lack of data sharing by government with UN agencies, data is collected and maintained mainly by UN agencies and their partners. UNHCR’s own database provides an insight into reporting rates for male and female survivors: while 80% of survivors of SGBV are female (60% women and 20% girls), 20% of the registered cases are male. Men and boys most frequently report sexual harassment in informal workplaces by members of communities. According to Ms. Velieceoğlu Yonca, this relatively high rate of reporting – particularly high among the LGBT+ group – is probably due to the safe spaces provided by UNHCR for the conduct of refugee status determination interviews.

Since 2003, sexual violence response for refugees in Turkey is structured around a multi-sectoral coordination mechanism managed by an SGBV inter-agency working group that convenes in monthly meetings in the capital Ankara and, since 2015, also in sub-working group meetings at the regional level including in Gazantiep[3]. SGBV Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) have been developed by UNHCR and UNFPA in 2016 and are awaiting endorsement from the government. In terms of outreach, representatives from UNFPA, government, municipal and humanitarian partners are present in 19 provincesin Turkey, where a total number of 35 women and girls’ safe spaces, 4 youth centres, and 20 social service centres constitute the backbone for GBV service provision. Service provision includes provision of protection assistance and case management services and awareness raising on physical and sexual violence.

A wide range of general challenges were highlighted for the identification of all SV survivors and the provision of sexual violence responses in Turkey. These relate to issues concerning humanitarian space and challenges related to the high mobility of refugees in urban areas which limits the possibilities for survivors’ identification. In addition, language barriers limit survivors’ access to services as well as the lack of awareness of rights and services, the lack of appreciation of the rights of refugees by legal practitioners and the absence of dedicated funds for SV/GBV response pose other impediments. The dearth of data-sharing by the Turkish government with UN agencies on statistics and limited identity protection-sensitive institutions were particular concerns. The issue of mandatory reporting for sexual violence prescribed by law for medical personnel in health facilities was identified as a considerable barrier for survivors’ access to medical services. Moreover, implementation (especially of the SGBV legal framework) remains problematic. Presenters emphasised that some barriers are specific for male survivors, including the limited capacity and expertise in providing services for male and LGBT+ survivors and particularly-high underreporting due to fear of stigmatisation and mistrust.

Numerous good practices and positive developments and efforts in the sexual violence response area were identified by UNFPA and UNHCR. Notably, the training of almost 2,000 doctors, midwives and other medical and translation personnel in SV/GBV medical care provision; a recent partnership with the Turkish bar association to increase the availability of legal assistance to survivors; the provision of several Arabic interpreters to refugee shelters; the activation of a national free-toll helpline number to facilitate provision of support and referrals; and finally, the creation of a website which contains informative and educational materials on SV/GBV. Provision of safe spaces for women and girls have proven crucial to the protection and empowerment of women and girls affected by the Syrian crisis.

Further, Ms. Velieceoğlu Yonca said that UNHCR Turkey Ankara office recently started a first-time dedicated SGBV Participatory Assessment in September 2018 of nearly 250 individual men, boys, girls and women through focus-group-discussions and semi-structured interviews in six locations with highest SGBV occurrence in Turkey (according to UNHCR records). The assessment seeks to understand personal and community level risks, perceived physical safety and security in the given provinces, occurrence of genderbased violence incidents, accessibility and effectiveness of response mechanisms, any available capacities within communities and prevention and mitigation measures. A report on the results of the assessment would be published towards the end of the year.

Certain specific efforts have been focused on men and boys and LGBT+ individuals. Resettlement is considered a strong avenue for SV/GBV survivors, especially LGBT+ individuals who are exposed to SV/GBV and who have limited access to support in Turkey. The provision of targeted cash for protection support for most at-risk individuals and groups, including transgender individuals, who often face specific challenges in finding accommodation solutions is an important initiative. Focused support for LGBT+ has been prioritised given risks and discrimination faced by these individuals.

The creation of specific space and activities for men and boys in youth centres was also raised as an effective way to provide a safe and confidential environment to facilitate trust-building and potentially disclosure. Livelihoods and economic empowerment initiatives, which include access to language courses and job opportunities, aim at facilitating survivors’ and at-risk individual’s self-reliance and prevent forms of SV/GBV such as survival sex and other forms of sexual exploitation often fuelled by economic needs.

The presentation concluded by identifying national ownership and state-owned initiatives as a key step towards sustainability.

Session III. Examining the landscape of responses to sexual violence in Afghanistan

Dr. Abdul Rasheed, MD, MPH, Executive Director, Youth Health and Development Organization (YHDO)

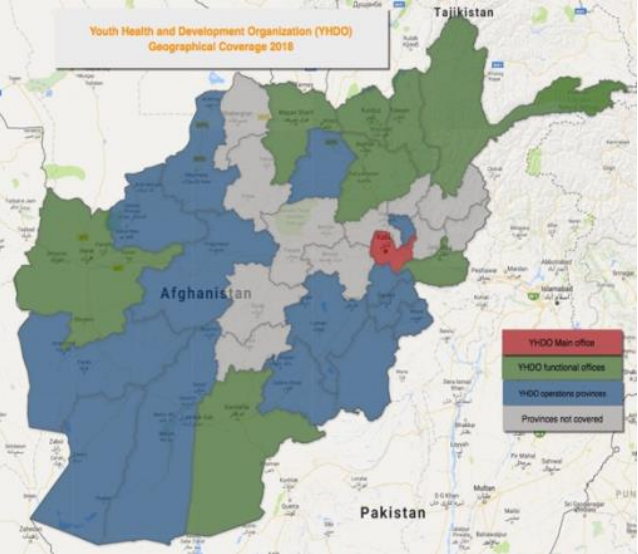

Dr. Rasheed presented on the work of Youth Health and Development Organisation (YHDO), an NGO that focuses on service provision to youth and other marginalised groups (e.g. MSM, bacha bazi victims, transgender community etc.) in 21 provinces in Afghanistan (indicated in red, green and blue in the map), with strong healthcare and protection and justice components and a developed research and advocacy approach. They also have a particular focus on the sexual health of marginalised youths. YHDO’s partners include the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, groups working on martyrs and disabled sections of the population, the Child protection network, and national action coordination group, Children rights advocacy forum and the Afghanistan network for combating trafficking in persons.

Dr. Rasheed provided a brief overview of the political and economic context in Afghanistan which has been characterised by a longstanding conflict and endemic socio-economic problems that continue to cause daily life loss, widespread human rights violations and high rates of sexual and gender-based violence.

While available data shows high rates of SV/GBV among women – with 85% of Afghan women reported that they had experienced physical, sexual or psychological or forced marriage, and 2,000 women and girls who are estimated attempting suicide each year due to domestic violence and early marriages. YHDO research among children shows high rates of sexual violence against children, including boys. Sexual violence against children in Afghanistan occurs in a context of high vulnerability for minors, where 40% of children have no access to schooling and 25% children are working in jobs that can lead to death, injury, illness and a high percentage are victims of early marriage.

Dr. Rasheed expounded on the reported practice of bacha bazi (‘boy play’ in Persian), a form of sexual exploitation perpetrated by adult men in positions of power who use boys and young men for social entertainment and sexual favours. In the largely under-researched practice of bacha bazi, which has a long history, boys are under the control of their exploiters – with the practice signifying power, honour, wealth and privilege. The more the number of boys the exploiters have under their control, the more power they are perceived to possess. Boys are often trained to dance in female clothes at parties and weddings. However, the practice is not uniformly manifest across the country. Illiteracy, poverty and lack of accountability were mentioned by Dr. Rasheed as being among the main causes of bacha bazi, which has numerous devastating impacts on children’s health and future perspectives.

Despite challenges, some responses were identified for bachas and other child victims of sexual violence in Afghanistan. These include child abuse case identification and referral services, specific MHPSS services for children, child friendly spaces and free legal counselling services. The shelter for boys in Kabul is an example of a gender-specific response that focuses on male survivors and is considered a good practice. Other good practices include a WHO-backed sexual violence treatment capacity-building initiative provided to health care providers as part of the child abuse response. In addition, peer outreach services by former bachas who identify other bachas who have been victimised and facilitate their access to psychosocial services, and legal aid provided by some organisations was identified as a good practice. The existence of advocacy groups on children’s rights in the country constitutes a forum through which such issues can be advanced.

Afghanistan’s legal framework criminalises bacha bazi related sexual violence and imposes sentences of up to three years for perpetrators of bacha bazi – with stronger punishments being issued where aggravating circumstances exist[4] . However, effective implementation of the law is hampered by an inefficient and corrupt justice system, and traditional socio-cultural norms on the other, whereby bacha bazi (or any other incidences of sexual assault against males) remains a taboo subject with serious societal stigmas that is not discussed, or actively tackled by the community and therefore not adequately addressed or effectively prevented.

A number of barriers prevent survivors from coming forward to seek help and denounce perpetrators. While the general dearth of response services and relevant professional expertise in large parts of Afghanistan as well as the challenging security situation in the country reflect deeper structural problems, other barriers include: bachas’ feelings of self-blame and guilt caused by the taboo and shame associated with the practice; the powerful status of perpetrators who are mostly wealthy businessmen and members of law enforcement bodies and/or well-armed groups; the lack of family support (often their tacit consent to the exploitation of boys); an absence of other supportive individuals around bachas who mainly live and work with their perpetrators in social isolation; and poverty which leaves bachas without any economic perspective or hopes for the future, should they decide to escape the exploitation.

Dr. Rasheed put forward several recommendations to increase the access to, and the quality of responses to child survivors. These include the need to initiate a dialogue on child abuse and bacha bazi in Afghanistan in order to break the silence and start unpacking and addressing this issue; increasing involvement of community members such as teachers and families to increase the identification of child survivors and facilitate their access to services. Public education campaigns and awareness efforts and engagement with community leaders including religious leaders were identified as key to start addressing social norms. Finally, a strong focus on the justice system and the protection sector which include advocacy efforts for the implementation of the new Penal Code and other legislation; the development of safe, ethical and survivorcentred ways to improve investigation of bacha bazi (especially given that some of the victims may still working for or are under the control of their exploiters); capacity-building for law enforcement agencies; and increased legal aid and protection options for children.

The research on the bacha bazi practice in Afghanistan that is currently being developed by YHDO and ASP, along with a planned nationwide research into the humanitarian responses by LSHTM and ASP will contribute to strengthening current knowledge of the practice and will hopefully identify ways to improve responses.

Session IV. Perspectives on barriers and good practices of the health humanitarian response to sexual violence and priorities for action

Ms. Nelly Staderini, Reproductive Health and Sexual Violence Advisor, MSF

MSF’s response to sexual violence is framed within the Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) policy and is considered as a medical emergency that requires an immediate response, possibly – for rape cases – within the first 72 hours that allow for HIV prevention and within the first 120 hours that allow for emergency contraception for women.

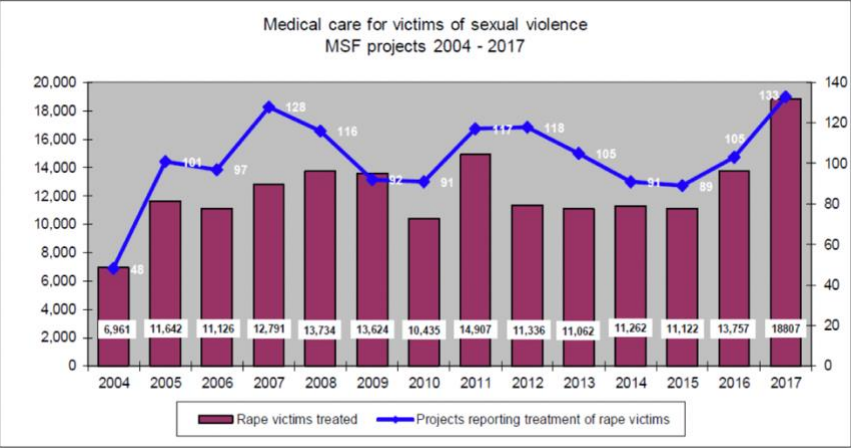

As Ms. Nelly Staderini illustrated, MSF data shows that in 2017, medical assistance to a total of 18,807 victims of sexual violence, mainly rape, within 133 different projects adopting either a vertical approach (i.e. focusing exclusively on sexual violence response, like the MSF project in DRC and Honduras or integrating SV care within wider health projects. These results represent a 70% increase since 2015.

Ms Staderini explained that male survivors are still under-represented in patients’ cohorts (globally around 10%), mainly due to lack of proactive efforts in creating adequate entry points, socio-cultural barriers to disclosure, to stigma and taboo, and lack of specific training for the staff to support their work with male survivors. However, increased attention and targeted strategies have allowed a number of projects to increase the number of identified male survivors, such as in certain projects in Zimbabwe, South Africa, Honduras and Greece. The most successful projects are the ones that have managed to move away from a predominantly female-focused model of care and have reinforced synergies with mental health activities, HIV testing and management of sexually transmitted infections (STI), and increased opportunities for contact with male patients.

Ms. Staderini mentioned ongoing challenges around the still limited access to care for some key groups, including male survivors, infant survivors, Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)/Domestic violence victims and the need to develop adequate intervention strategies in complex socio-cultural contexts like the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region and in migration contexts. The main challenges that are specific to care provision for male survivors in MSF are complex and go from the lack of assessments prior to project design and rollout, to difficulties in identifying male survivors through the current entry points in projects, from the challenge to respond to the complex needs of male survivors who suffered torture, to the existence of competing priorities in humanitarian settings. Ms. Staderini also mentioned other global challenges such as the general fear that a focus on male survivors will divert the attention in the political agenda, and donors’ funding, from female survivors, and the lack of specific training to strengthen skills and competencies for responses to male survivors.

Ms. Staderini identified a number of good practices that MSF has been developing over the past years to increase SV care provision for all survivors. These are mainly centred on capacity-building of its staff and focused support to field operations. Field-based and online sexual violence-focused training programmes for both medical and non-medical personnel and the appointment of sexual violence focal points and roving implementing positions have proved very effective facilitators to trigger an increase in care provision and survivors’ numbers. Other good practices include internal knowledge-sharing and knowledge-building initiatives mainly through research and assessments. Today, improved data monitoring through individual patient data collection in databases, which allow for sex and age disaggregated data to be collected and analysed, is providing new opportunities for a better understanding of specific gaps and of the need to adapt project’s strategies and activities. Among the aspects that MSF plans to focus on to improve disclosure and responses for male survivors and other vulnerable groups are: strengthening the work around confidentiality on projects (in the training for staff, in designing a confidential patient pathway inside medical facilities, in safely storing sensitive data and patients’ files); exploring the various strategies to increase awareness and facilitating disclosure (systematic awareness, screening tools, embedding entry points for SV in a range of services to decrease stigma etc.); and providing adequate response with the availability of female and male staff and the set-up of a referral system for comprehensive MHPSS, social, justice and protection response. MSF will also focus on improved community education and engagement strategies, higher involvement of survivors in the design of targeted approaches and in the assessment of services and increased referral to income generating activities, which has been identified as particularly important for male survivors.

Ms. Staderini concluded by suggesting that participants listen to the podcast “Medical Care of Male Survivors of Sexual Violence in CAR” (link available here), produced by ASP with the participation of Catrin SchulteHillen, Head of MSF International Working Group on Reproductive Health and Sexual Violence Care. The podcast, released in June 2018, highlights the medical needs of male sexual violence survivors and the challenges they face in accessing care in situations of conflict.

Session V. Surviving neglect: the struggle for boys, men and fathers to heal from sexual violence and torture

Dr. Alexandra Chen, Trauma Specialist, Harvard University

Trauma specialist Dr. Chen shared with participants an insight into the risks, vulnerabilities, needs and realities faced by Syrian male survivors of sexual violence – particularly using the story of one of her Syrian patients, an 11-year old boy survivor.

She emphasised the need for in-depth research and investigations in all fields, including mental health, on the issue of male sexual violence in order to increase the understanding of male experience of sexual violence and better inform responses and service provision. She argued that preoccupation by practitioners on prevalence rates of sexual violence seem unnecessary and that the focus should be on the fact that such abhorrent crimes occur – which was bad enough. She also highlighted the need for practitioners and experts to deconstruct their assumptions about gender and male survivors based on the little knowledge of their specific needs and realities. Acknowledging the fact that the current knowledge on male survivors is generally weak is a helpful starting point for practitioners – “How do we know what we do not know?” she repeatedly asked participants, highlighting that the lack of acknowledgement that “we do not know” how to deal with male sexual violence constitutes one of the most serious barriers for male survivors’ increased access to care.

Dr. Chen pointed out to some good practices that can help practitioners identify male survivors, including the reading of silent and clinical signs, and providing information in safe and confidential male spaces like ‘shisha tents’ or gyms in refugee camps, where male community members can bond, share experiences and learn of existing responses. She emphasised the need for practitioners to provide male survivors the time to acknowledge their victimisation (especially given that “their disclosure is a luxury”) before accompanying them along the path of empowerment.

During a short discussion following the presentation, participants discussed the numerous challenges that impede the identification of male survivors and provision of adequate responses. After sharing experiences, participants agreed on the need for practitioners not to dismiss or neglect male survivors’ perspective and wishes and maintain a non-judgemental stance by resisting the imposition of one’s cultural values.

Session VI. Comprehensive Coordination Support to Child and Adolescent Survivors of Sexual Abuse in Emergencies Initiative

Mr. Bilal Sougou, Deputy Coordinator, Child Protection AoR, UNICEF

After providing participants with a brief overview of the structure of the humanitarian cluster system and in particular on the GBV and Child Protection (CP) sub-clusters, Mr. Sougou focused his attention on the recent Comprehensive Coordination Support to Child and Adolescent Survivors of Sexual Abuse in Emergencies Initiative (referred to as the “Child survivor’s initiative”), aimed at improving quality of and access to services for child and adolescent survivors of sexual abuses in emergencies.

Acknowledging the central role that CP and GBV practitioners play in responding to sexual abuse and the need for timely and effective coordination among all emergency response actors to ensure access to specialised services for child survivors, the initiative focuses on building capacities and improving coordination among GBV and CP practitioners and services to strengthen and manage quality response services – especially clinical, MPHSS, and case management – that support children, adolescents, and their caregivers.

Currently piloted in Niger, Sudan, Iraq and Myanmar and supported by partners such as UNICEF, International Rescue Committee (IRC) and Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), the Child Survivor Initiative aims at: providing practitioners an enhanced knowledge base on responding to child and adolescent survivors (both male and female) of sexual abuse in emergencies; providing coordination mechanisms improved service coordination for child and adolescent survivors; and strengthening the global commitment to improve the quality of and access to child and adolescent survivors of sexual abuse, in emergencies.

Day 2 – Friday 12 October

Barriers for sexual violence survivors from a WHO perspective

Ms. Elizabeth Roesch, Technical officer, WHO

WHO Technical officer Ms. Elizabeth Roesch presented WHO’s perspective on barriers faced by survivors to medical services in emergency settings. Ms Roesch emphasised that WHO’s health approach to gender-based violence in emergency focuses on women and girls as the most vulnerable group, while also including guidance to respond to the needs of children (including boys), and male survivors of rape. WHO clinical guidelines are designed to guide clinicians to serve every survivor; while specific guidance is provided on rape for children and male victims, women-centred care remains a strong foundation for the approach for all survivors, including males.

In emergency settings, the main barrier to sexual violence and GBV care is primarily the lack of GBV services (in some countries only around 10-15% of health facilities can provide clinical rape management). Other barriers include stigma, and other obstacles, such as the lack of services for victims of torture, and the limited time that medical practitioners often have for survivors’ care and support especially in emergency high-pace settings.

Ms. Roesch identified the need to have more GBV services as crucial. She emphasised that continuous and sustained efforts need to be focused on training service providers on skills, attitudes and values to break internalised stigma and build empathic capacity to provide care for all survivors. Knowledge also needs to be built on existing guidance for male survivors, and understanding what the best entry points for care are for this group. . More focused attention and efforts are also needed to improve responses for intimate partner violence (IPV) and for producing more guidance on the mental health and psychosocial aspect of care.

A short discussion followed Ms. Roesch’s intervention where participants highlighted some additional challenges, including ways to ensure continuation of care for survivors in unstable and emergency settings. On a different point, Lead Doctor for Forensic Medicine at the Haven in the UK, Dr. Muriel Volpellier pointed out the need for training for doctors on sexual violence forensic examination and documentation. Participants agreed on the importance that any training to medical personnel is followed by practice for skills to be acquired and maintained.

Developing a framework to improve responses for male survivors of sexual violence in conflict

Dr. Mazeda Hossain, Assistant Professor of Social Epidemiology, LSHTM

Dr. Mazeda Hossain opened the second part of the workshop that focused on identifying elements and aspects to be considered for the building of the framework to improve responses for male survivors in conflict settings.

Dr. Hossain provided a brief introduction on methodological considerations for building a conceptual framework. She explained how ASP and LSHTM foresee addressing the so-far identified knowledge gaps related to response to CRSV against men and boys – mainly limited evidence and research on appropriate care and limited evidence and research on barriers to care – using a public health approach which builds on the learning and practical knowledge from work with female survivors to develop a framework for national actors to assist male survivors.

As Dr. Hossain asked the experts to consider several questions to explore what factors need to be considered when developing a country-level response framework for male survivors of conflict-related sexual violence. These questions included.

- What health and protection outcomes are important in the short and long-term among male survivors of conflict-related sexual violence?

- What do we need to have in place to achieve our outcomes? (i.e., resources, services, policies, etc.)

- What factors might influence the ‘trajectory’ of the predicted framework?

Group discussions

All participants were allocated to the two thematic work groups listed below and asked to hold discussions on their respective sector’s existing problems and needs, and possible responses for their sector, identifying key actions to be implemented. Country representatives from CAR, Afghanistan and Turkey had a presence in both groups to ensure that country-specific challenges and potential ways forward were considered in the debate. Each group summarised their findings and presented it to all workshop participants on Day 2.

The two groups were:

- Medical and MH/PSS response

- Justice, Legal and other forms of protection

The two groups held separate half day discussions on Day 1 and 2 before sharing their reflections and action plans with the rest of the participants. Discussions were supported by a sector-specific document provided by organisers which suggested specific guiding questions for each area. A set of recommendations which emerged from discussions from both groups constitutes the first consensus on parameters and scope for the conceptual framework which ASP seeks to develop.

Summary of discussions of Group 1 – Medical and MH/PSS response

Problem analysis

The three countries faced similar challenges related to ensuring safe and confidential access into health facilities for male survivors. Discussions developed around how it might be possible to establish private, confidential and safe entry points in health/MHPSS facilities, and what needs to be established in the facility design and patient pathway in order to facilitate confidential access and/or disclosure by male survivors in a non-stigmatising way. Accessibility issues in CAR were identified to be the most challenging due to the chronic lack of basic infrastructure in most regions.

Besides, the physical design of the structure itself, limited staff skills and competences were perceived as the main challenge and a key issue to build on and develop. Health and MHPSS staff in the three countries are believed to often lack the basic skills to identify clinical and silent signs in male survivors and to respond to a potential disclosure in an appropriate way and to provide adequate and quality care.

Health staff face many common challenges in all three countries. While technical skills on how to conduct examinations and provide treatment plans for male survivors are a gap for many health providers and there is a dearth of specific training or tools available on how to work with men and boys, staff’s personal attitudes and belief systems appear to be an even more important issue to work around. Internalised rigid social norms, stereotypes and attitudes around sexual violence, may prevent health providers from offering the compassionate, non-judgmental and empathic survivor-centred care and support that male survivors need.

Similar issues were raised for MHPSS staff, although a major additional challenge was identified in the insufficient number of trained counsellor and psychotherapists in the three settings, particularly in CAR and Afghanistan.

Specific barriers and challenges for specific groups such as LGBT+ were also analysed especially in Turkey and Afghanistan, where trans and other gender non-confirming individuals are at risk of specific discrimination by the law and by society and may face increased vulnerability and exposure to risks. The group discussed at length the tensions that exist between legal mandatory reporting obligations for medical personnel existing in the countries and survivors’ confidentiality and best interest. This issue was particularly recognised as problematic in Turkey and Afghanistan, where medical personnel are required by law to report sexual violence to the police. Such requirements may not respect the wishes, choices and best interests of survivors and be incompatible with a survivor-centred approach if the legal procedures are harmful or re-victimising for the survivor. The situation is particularly difficult in cases of child survivors, for whom health personnel, though legally obligated, may breach medical confidentiality by informing the family or risk putting the child survivor in further danger. The need to reconcile legal and ethical obligations was a prominent point that was debated.

Recommendations

In the light of the above challenges, gaps and problem analysis, several recommendations were put forward by the group. The main ones include:

- Ensure that all medical facilities are equipped with private, confidential and safe spaces which are easily accessible to all survivors of sexual violence to disclose and access care. Confidential entry points and internal patients’ pathways need to be established and formalised in each health/MHPSS facility and the specific needs for particularly vulnerable groups such as children and LGBT+ individuals also need to be taken into account. The free-toll telephone helplines for GBV cases in CAR are one example of a good practice that could be built on and considered for the other settings.

- Ensure Medical and MHPSS practitioners are sufficiently trained on how to identify signs that might be indicative of sexual violence suffered by male survivors (such as chronic pain, psychosomatic pain, and other clinical and silent signs) and respond to male survivors’ disclosure with an appropriate psychological/emotional response. Training for medical, psychological and social workers and staff in Psychological First Aid for sexual violence survivors and male survivors specifically, and on how to safely and confidentially refer a survivor to ensure his access to mental health and other services, may prove crucial in the three settings. Specific training for mental health personnel on specialised support for survivors is also of paramount importance.

- Sufficient space in training and capacity building initiatives need to be dedicated to exploring health providers’ attitudes, fears and belief systems and address/deconstruct potential problematic tensions between individual’s attitudes and values and the need to provide survivors a patientcentred, non-judgmental and unconditional care and support. Translators / interpreters / cultural mediators also need to be well trained to be supportive of links between providers and the survivor.

- Ensure that medical and MHPSS personnel are trained on the country’s legal framework and work with child protection and legal experts to be able to navigate the complexities around the tension between reporting to authorities and survivors’ confidentiality, informed consent and safety.

- Specific guidance is needed on how to work with children and in particular on issues related to child consent, confidentiality and safeguarding issues in the relation with them and with the family, both in case the family is the place of the abuse and in those where family is a crucial support system.

- Robust community work needs to be strengthened in all countries. Community awareness and engagement work needs to ensure that information on how to safely and confidentially access response services reaches all groups including the most vulnerable such as children and LGBT+ individuals. Non-structured community support, via community members and community-based mechanisms (e.g., listening centres) also need to be strengthened as they can constitute primary PSS mechanisms in all communities to support survivors. Specific work with community leaders including religious leaders may prove crucial to also help fight stigma and build support and acceptance of survivors in the community.

Summary of discussions of Group 2 – Justice, Legal and other forms of protection

Problem analysis

A general lack of shelter and safe accommodation options for male survivors, with no options to protect survivors from repeated exposure to violence and make them feel safe, was identified in all three case country settings. The need for safe accommodation appears particularly urgent in CAR and Afghanistan and specifically for children, including demobilised children and unaccompanied children, who are often placed in reception centres or detention centres with adults. These countries offer no interim or alternative care and age-appropriate options. Transgender people have been identified as a particularly vulnerable group, particularly in Turkey and Afghanistan. While safe accommodation options exist in Turkey, challenges have been identified in their overall capacity and in the poor information available on how to access it. Cash for protection programmes also exist in Turkey, which can offer a practical way for survivors to pay for their accommodation.

Access to justice and accountability were discussed at length since they represent key challenges in the three countries, where a general lack of trust in authorities, judicial system and law enforcement bodies coupled with inadequate skills and competencies (because of the lack of exposure, experience and training) of these bodies undermine any real access and positive outcome for survivors. Difficult access to civil documentation in the three countries also represents an additional challenge for people who want to access justice as well as a range of services and rights. Children’s access to justice in all three countries is hampered by the fact that authorities and service providers possess little or no skills and competence in making best interest determination (BID) for them.

Moreover, even when the limited cases, especially those concerning sexual violence against males are before legal practitioners (after surmounting various preliminary barriers ranging from reporting to narrow conceptions), further challenges abound culminating in inconsistent and underwhelming prosecutorial attention as well as stultifying judicial decisions.

The almost complete lack of livelihood options was identified as one of the contributing factors to exposure of survivors to risks of further victimisation and exploitation. For boys, the lack or very limited availability of vocational training and educational options prevent effective access to the labour market. These gaps can be therefore seen as a general lack of sufficient prevention measures.

Recommendations

Recommendations put forward by the group based on the above problem analysis include:

- Ensure sufficient safe accommodation options are available in all countries for male survivors, particularly for the most vulnerable cases including children who may need special accommodation separate from adults, and LGBT+ who face particular risks of re-victimisation and discrimination. Good practice identified in Turkey where cash for protection and relocation is offered to LGBT+ individuals could be built on and expanded. Also, ensure better access to information on how to access safe accommodation options, keeping in mind that some effective mechanisms like hotline or mobile apps – used in Turkey – might involve safety risks for survivors. Monitoring of detention facilities, including through coordination with protection actors, can be effective in ensuring that children including CAFAAGs and other children in detention are separated from adults.

- Ensure capacity-building initiatives are designed and offered to justice actors and law enforcement bodies, including police and detention authorities, to ensure they have the necessary skills and competencies to deal with male survivors and to facilitate trust-building with them. Specific skills are needed in particular to deal with child survivors, for example BID capacity to ensure that the best interest of children is prioritised in all circumstances.

- Ensure a gender-inclusive analysis of CRSV by legal and justice practitioners – at national and international levels. This would require interpreting and understanding physical and psychological sexual violence that targets males and females, concurrently, successively, consequentially or alternatively. There also needs to be adequate, non-judgemental and neutral space in training and capacity building initiatives that commits to exploring their attitudes, fears and belief systems and analyse/address potential difficult tensions between individual’s viewpoints and beliefs and the need to provide full and impartial justice. Translators / interpreters / cultural mediators working alongside the legal and justice practitioners also need to be included as partners, and trained if necessary to appreciate and be supportive of the process.

- Ensure sufficient livelihood and economic empowerment opportunities for male survivors, including cash for work or livelihood programmes to facilitate the economic empowerment of survivors and prevent further exposure to harm and exploitation. Access to education and vocational training are also recommended for boys (and girls).

- Work with the community (whilst being culturally-sensitive) to strengthen community-based components such as outreach and awareness, peer support, and community-based protection mechanisms are also recommended in all countries to ensure basic psychosocial support and protection to all survivors.

Conclusion and follow-up

The workshop achieved its core objectives of: (a) sharing research findings, including good practices and clearer identification of barriers which have emerged from ASP research to date; (b) examining available responses for survivors of sexual violence in Central African Republic (CAR), Turkey and Afghanistan and deepening our understanding of barriers and good practices for men and boys in each context; and (3): developing a consensus on parameters and scope of the conceptual framework.

Crucially, the workshop catalysed a collective and constructive process of discussion and information sharing which will feed into developing a conceptual framework to understand barriers to medical and MHPSS care for male survivors. The active participation of all attending organisations was a tangible sign of both the widespread acknowledgment of the importance of this problem and a sign of the determined commitment by all stakeholders, to address this issue.

Based on the workshop conclusions and the bilateral discussions and consultations with several participants and organisations, All Survivors Project and LSHTM suggested the following next steps:

- Creation of Research Advisory Group (ToR to be developed)

- Development of a literature review

- Development of a Draft Response Framework and identification of potential areas for adaptations by case countries

- Research proposal development for funding case country studies

- Case country studies to refine country-level response frameworks

- Research funding to identify and test MHPSS adaptations and guidance development

All Survivors Project reiterates its commitment to address conflict related sexual violence in CAR, Turkey and Afghanistan by continuing to work in partnership with the human rights and humanitarian community, as a promoter and facilitator of methodologically sound approaches, to build a stronger and more effective response to sexual violence for all survivors of sexual violence from a survivor-centred perspective.

All Survivors Project also reaffirmed its conviction that a stronger focus on CRSV against men and boys should not take away existing attention from the need for better response to women and girls, but rather focus on the needs of all survivors. Indeed, all the sexual violence must be accounted – because when they are collectively analysed, it reveals a broader pattern of conduct, than when examined independently. All the CRSV must be redressed legally and serviced through humanitarian relief.

All Survivors Project remains grateful to the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) for its continuous and generous support, and to UNHCR, UNFPA, UNICEF and all its partners for their cooperation and commitment and to every organisation and participant at the workshop for their active contribution to the discussions.

ANNEXES

Annex I – Workshop programme

Annex II – List of participants

Annex III – ASP resources and material

All Survivors Project reports

- “Destroyed from within. Sexual violence against men and boys in Syria and Turkey” (available in English), September 2018 https://allsurvivorsproject.org/country/syrian-arab-republic/

- “I don’t know who can help. Men and boys facing sexual violence in Central African Republic” (available in English and French), March 2018 https://allsurvivorsproject.org/country/central-african-republic/

- “Legacies and lessons: sexual violence against men and boys in Sri Lanka and Bosnia and Herzegovina” (available in English), May 2017 https://allsurvivorsproject.org/country/former-yugoslavia/

All Survivors Project documentary videos

- “No one cares about them: sexual violence against men and boys in Syria and Turkey” (available in English and Arabic), September 2018 https://allsurvivorsproject.org/issue/documentary-no-one-cares-about-them-sexual-violenceagainst-men-and-boys-in-syria-and-turkey-6-september-2018/

- “Hidden crisis in CAR: sexual violence against males in Conflict” (available in English, French, Italian), December 2016 https://allsurvivorsproject.org/issue/hidden-crisis-in-car-sexual-violence-against-males-in-conflict/

All Survivors Project’s submission to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, March 2018

All Survivors Project’s Contact Details

- Charu Lata Hogg, Director – Hoggc@allsurvivorsproject.org

- Patricia Ollé, Project Coordinator – info@allsurvivorsproject.org

- Carla Ruta, Head of Research – rutac@allsurvivorsproject.org

- Laura Pasquero, Senior Humanitarian Advisor – PasqueroL@allsurvivorsproject.org

Social Media

Connect with us on Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn for updates.

If you would like to receive notification of new reports and other news please visit our website at www.allsurvivorsproject.org and subscribe to our mailing list.

London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine’s Contact Details

- Dr Mazeda Hossain, Assistant Professor – Mazeda.Hossain@lshtm.ac.uk

All Survivors Project (ASP) conducts research and advocacy and facilitates inter-disciplinary dialogue and learning to improve the global response for every victim/survivor of sexual violence in situations of armed conflict and forced displacement. ASP is an independent, international organisation working with male survivors of sexual violence, governmental and non-governmental stakeholders to strengthen national and international efforts to prevent and respond to conflict-related sexual violence and to ensure that the rights of victims are fulfilled, and the dignity of all survivors is respected and protected.

References[+]

| 1↑ | Such as the Law n° 06.032 du 27 Décembre 2006 on protection of women against violence in Central African Republic, the Interministerial Order No. 007 of 21 April 2005 establishing the National Committee to Combat Harmful Practices against Women, or the Law N° 06.005 of 20 June 2006 (« Bangayassi ») on Reproductive Health. |

|---|---|

| 2↑ | GBVIMS data: 2016: 11,110: total, female: 86%, male: 14%, minors (0-18yrs): 17%, adults: 83%. GBVIMS data: 2017: total: 8,321, female 90%, male: 10%, minors (0-18yrs): 14%, adults: 86%. |

| 3↑ | As per its TORs, the WG aims at identifying key issues and challenges regarding GBV response offer and share best practices among its member to better face challenges and obstacles in implementation. |

| 4↑ | For example, if the perpetrator keeps more than one child; if the victim is under 12; if victim is financially dependent on perpetrator; if the crime has caused physical or psychological harm to the child etc. |