Acknowledgments

All Survivors Project (ASP) and Youth Health and Development Organization (YHDO) would like to thank the victims/survivors of sexual violence, healthcare providers, community health workers and government and non-government stakeholders who participated in this research and shared their perceptions and experiences. The report was authored by Julienne Corboz. Layout and production assistance was provided by Roberto Thillet. ASP and YHDO, and the author of this report, are extremely grateful to the stakeholders who participated in the National Advisory Group, particularly those who peer reviewed and provided valuable feedback on drafts of the report, including: Taiba Jafari, Director of the Gender Directorate, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Ministry of Public Health; Najeebullah Zadran Babrakzai, National Coordinator for the Rights of Children, Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission; and Palwasha Aabed, Child Protection Officer, United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan. The author is also grateful for peer review and feedback from the ASP and YHDO team. All Survivors Project, and not the peer reviewers, is responsible for the final content of this report.

Cover illustration: Brian Stauffer

© 2021 All Survivors Project and Youth and Development Organization.

Acronyms

ASP – All Survivors Project

BHC – Basic Health Centre

BPHS – Basic Package of Health Services

CHC – Comprehensive Health Centre

CHW – Community Health Worker

CPAN – Child Protection Action Network

CRSV – Conflict-related sexual violence

DoPH – Department of Public Health

EPHS – Essential Package of Hospital Services

ER – Emergency room

EVAW – Elimination of violence against women

FLE – Family Life Education

FPC – Family Protection Centre

GBV – Gender-based violence

HIV – Human Immunodeficiency Virus

HSC – Health Sub-Centre

IDI – In-depth interview

KII – Key informant interview

MoE – Ministry of Education

MoLSA – Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs

MoPH – Ministry of Public Health

MSM – Men who have sex with men

NGO – Non-governmental Organisation

OPD – Outpatient department

SOGIESC – Sexual orientation, gender identity and/or expression, and sex characteristics

SOP – Standard operating procedure

STI – Sexually transmitted infection

UNFPA – UN Population Fund (previously UN Fund for Population Activities)

YHDO – Youth Health and Development Organization

WHO – World Health Organization

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

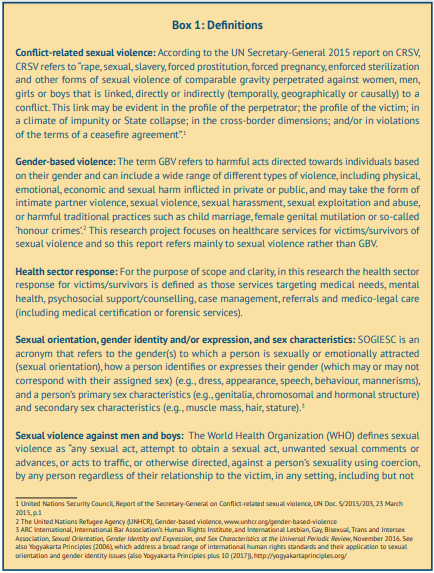

Women and girls in Afghanistan are extremely vulnerable to gender-based violence (GBV) and face substantial barriers accessing healthcare facilities to seek help after such violence. This is widely known. Much less is known about sexual violence committed against men and boys, the barriers male victims/survivors face accessing healthcare facilities, or the quality of healthcare provision available to them.

This report presents the findings of research conducted by international non-governmental organisation All Survivors Project (ASP) with its partner on the ground in Afghanistan, Youth Health and Development Organization (YHDO). With this research, ASP and YHDO seek to:

- Cast light on the healthcare needs and experiences of male victims/survivors of sexual violence in Afghanistan and the barriers they face accessing quality healthcare services.

- Understand the practices of healthcare providers, and the barriers they face, in supporting male victims/survivors of sexual violence.

- Learn about how a survivor-centred approach to healthcare provision is applied in Afghanistan in the case of male victims/survivors.

- Produce a set of recommendations for enhanced survivor-centred healthcare services for male victims/ survivors of sexual violence that can be used to develop a tool for the health sector.

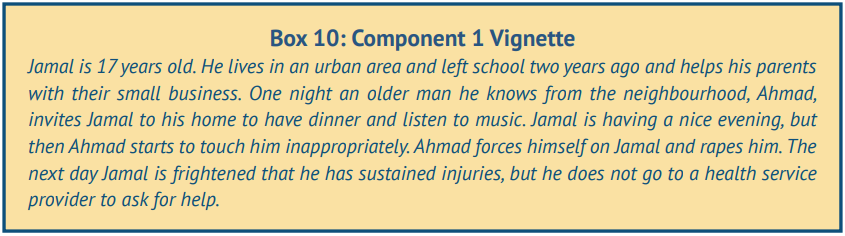

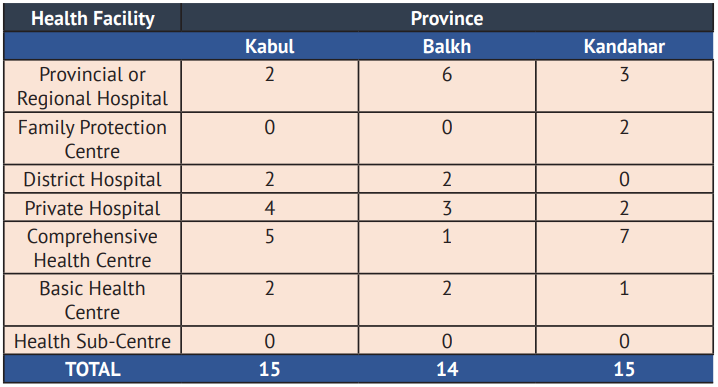

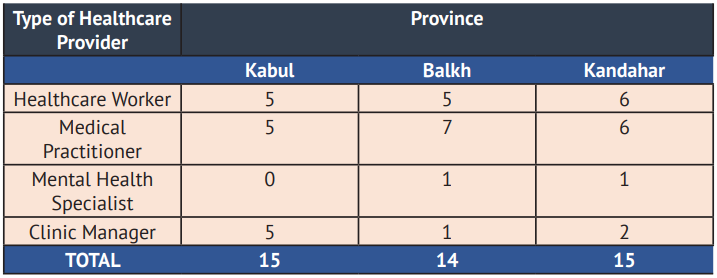

The research was conducted in three provinces of Afghanistan: Kabul, Balkh and Kandahar, with data collection conducted during the second half of 2020, under special measures adopted in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The research adopted a qualitative approach involving four key methods:

- A desk review, including literature on sexual violence against men and boys and the health sector response, with a focus on evidence from Afghanistan.

- A stakeholder mapping to identify existing systems of healthcare response that include coverage of male victims/survivors, conducted predominantly through a desk review of online documents.

- Ten key stakeholder interviews were conducted with a range of individuals, from government, national and international NGOs, and UN agencies.

- Ninety-seven in-depth interviews were conducted – 27 with male victims/survivors of sexual violence, 44 with healthcare providers working in different types of static health care facilities, and 26 with community health workers.

The results of the ASP/YHDO study suggest that the health sector is currently a vastly underused entry point for male victims/survivors of sexual violence in Afghanistan, due to multiple and cumulative barriers preventing them from accessing healthcare services.

Before elaborating on these barriers, the report outlines the structure of Afghanistan’s healthcare system under which services operate at three main levels: community, district, and provincial/regional. There is an upward referral system under which more complex cases are referred to higher levels where there are larger numbers of healthcare staff, services and resources. In addition to the different types of static and mobile health services overseen by the Ministry of Public Health, some health facilities are run privately.

A range of services has been developed specifically to address the health care needs of victims/survivors of GBV, although these are largely directed towards women and girls. Thirty-seven Family Protection Centres (FPCs) have been established in 26 provinces and form part of a wider multi-sector response to GBV programme that provides health, police and justice services for victims/survivors, with FPCs providing the primary entry point. FPCs are located in government provincial and regional hospitals to ensure their sustainability within the national health system, and provide support to victims/survivors, including basic health services, medical support, psychosocial counselling, legal support, help in collecting evidence and providing referrals to other services. FPCs may not be accessible for all victims/survivors, particularly those who live in more remote locations. Consequently, some NGOs working in humanitarian response now send mobile outreach teams to visit communities and provide GBV services and referrals.

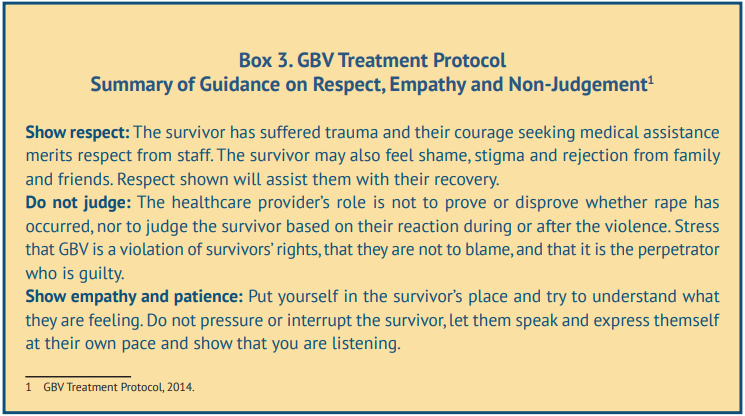

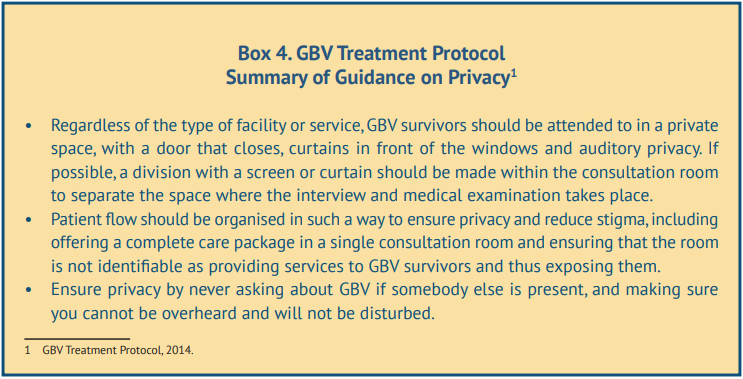

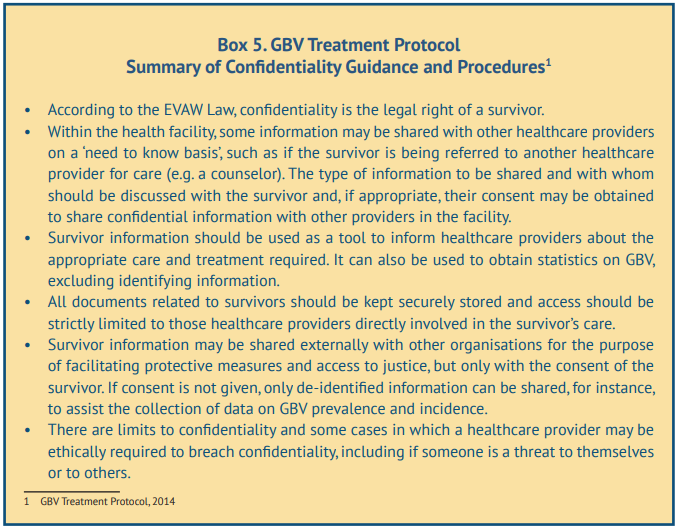

Several resources have been developed by a range of organisations to facilitate higher quality of health care provision for victims/survivors of GBV, although, much like GBV services, these resources are largely directed towards women and girls. These include a training manual for health professionals on a traumasensitive approach to care for victims/survivors of GBV in Afghanistan; Standard Operating Procedures for Healthcare Sector Response to GBV; and the GBV Treatment Protocol for Healthcare Providers in Afghanistan (GBV Treatment Protocol).

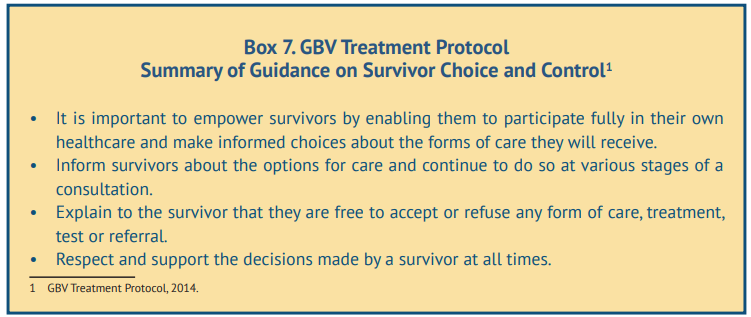

The GBV Treatment Protocol contains comprehensive information and guidance on a range of topics, including legal frameworks and requirements, patient flow, confidentiality, documentation and reporting, survivor-centred care, identifying and responding to patient disclosures of GBV, and different types of care for victims/survivors. The Protocol is intended to provide guidance on healthcare response to all GBV victims/ survivors; however, although it notes that men and boys, particularly adolescent boys, can experience sexual exploitation and violence, the Protocol emphasizes that women and girls are disproportionately affected by GBV and the Protocol is largely targeted towards them.

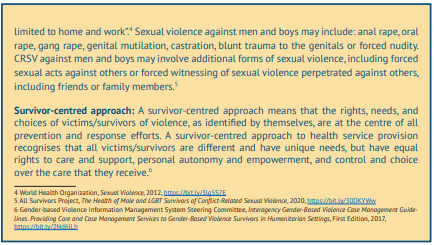

The barriers preventing male survivors/victims of sexual violence accessing quality healthcare services are detailed in the ASP/YHDO report and are outlined in Table 1 below. Adopting a social ecological model of public health, the barriers are differentiated by level, of which there are five: individual, interpersonal, community, organisational, and structural. These barriers do not operate in isolation and male victims/survivors face multiple, mutually reinforcing barriers, making access to healthcare services extremely challenging.

Poverty and inability to pay for services, including fees in private healthcare facilities (which are often perceived to be of higher quality and safer) and for medications or other services in government facilities, were highlighted as important barriers. Further, victims/survivors with poor socio-economic status living in rural or remote areas were reported to struggle to pay for transport to access a healthcare facility at the district level or in the provincial centre.

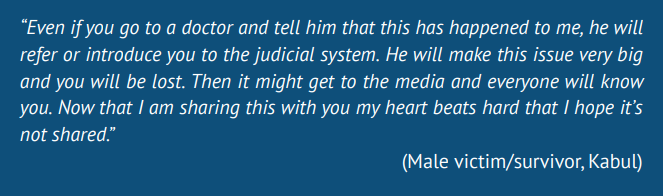

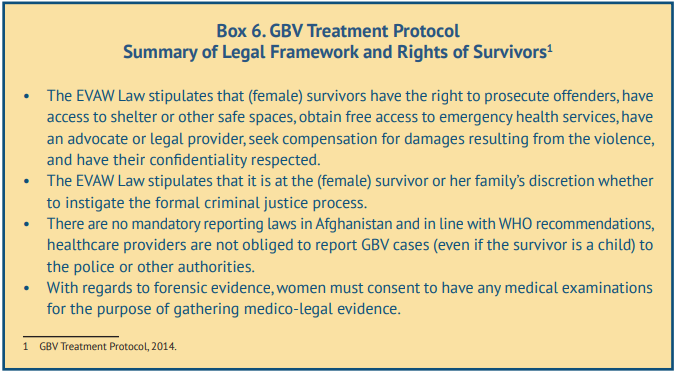

The legal and policy environment in Afghanistan in relation to male victims/survivors of sexual violence appears to be an important structural barrier to help-seeking. Despite no legal requirements for mandatory reporting of GBV cases in Afghanistan, male victims/survivors reported strong fears that healthcare providers would disclose their case to judicial actors without their consent. These fears are likely linked to same-sex sexual acts being criminalised and concerns that, despite rape being criminalised under the Penal Code, healthcare providers will make judgements about whether sexual acts are consensual or non-consensual. The research found some examples, specifically in Balkh province, where this appears to be the case.

The research identifies several rape myths that circulate about why sexual violence against men and boys occurs. Male victims/survivors are more likely to reproduce victim-blaming discourses, perhaps due to internalised stigma and blame received from others. In contrast, healthcare providers are more likely to justify the behaviour of perpetrators by suggesting that social and cultural norms and practices, including expensive weddings and gender segregation, lead to men’s uncontrollable sexual desire. In either case, perpetrators are not portrayed as being actively responsible for the sexual violence they perpetrate, with the locus of responsibility being placed on victims/survivors and their families.

The ASP/YHDO report examines how communities might support male victims/survivors of sexual violence. It suggests that community health workers (CHWs) could play a role in supporting male victims/survivors and facilitating their access to health facilities, although there are gaps in CHWs’ knowledge of how to provide confidential and survivor-centred care. The report also suggests that community leaders, religious leaders and members of community health councils may also have a role to play in reducing barriers to male victim/survivors’ access to healthcare facilities by raising awareness of and preventing stigma against male victims/survivors and supporting them to access services. However, significant work needs to be done with community and religious leaders to challenge their negative attitudes and potentially violent behaviours towards male victims/survivors.

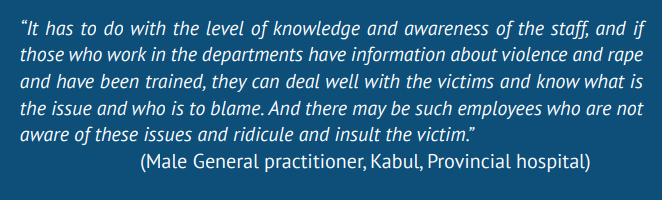

The report describes the perspectives of male victims/survivors and of healthcare providers on the care pathway for male victims/survivors in health facilities, and the typical experiences that men and boys might expect to have in receiving care, including survivor-centred care. The majority of the healthcare providers interviewed had knowledge about the characteristics of a survivor-centred approach and in most cases were able to articulate how such an approach would be implemented with male victims/survivors, even though few of them had ever provided services to a male victim/survivor of sexual violence.

The descriptions given by healthcare providers on how to implement such an approach were largely in line with the guidance provided in the GBV Treatment Protocol, despite few of them having been trained in the use of the Protocol and the Protocol being largely framed around the needs of women and girls. To identify and illustrate the extent to which current practices and systems to address the needs of male victims/ survivors are aligned with the GBV Treatment Protocol, the ASP/YHDO research findings are set alongside the guidance in the Protocol – including its guidance to ensure respect, empathy, and non-judgement, to ensure privacy and confidentiality, and in relation to the question of referrals to judicial actors, and of survivor choice and control.

Despite the healthcare providers’ overall knowledge of survivor-centred care, the report points to significant dissonance between their descriptions of the care they would provide to a male victim/survivor, and the treatment that male victims/survivors expect to receive. This could be due to victims/survivors being unaware of more recent advancements in health sector responses to GBV more generally. However, it may also be due to persisting gaps in healthcare providers’ attitudes, knowledge and practices with regards to male victims/ survivors of sexual violence.

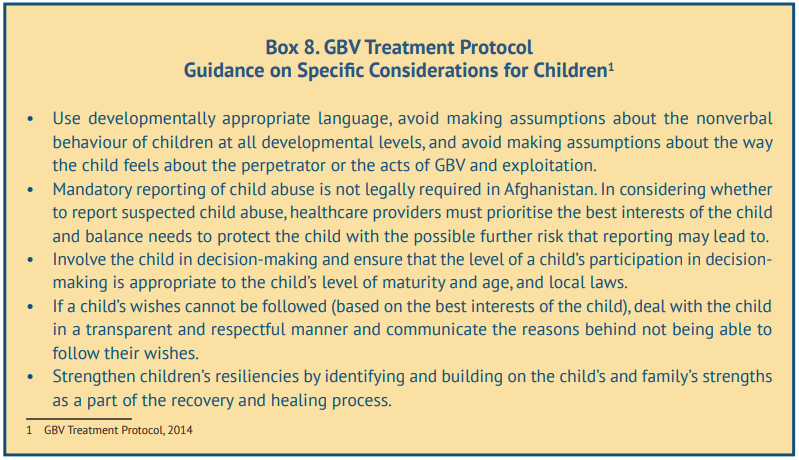

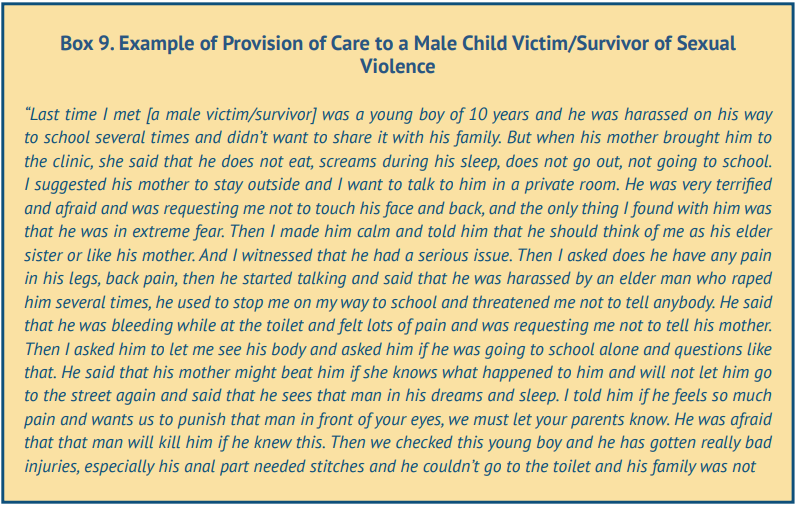

For ethical and safety reasons, the victims/survivors interviewed for this research were all adults, leaving an acknowledged gap in the research. However, several male victims/survivors disclosed that they had first experienced sexual violence as a child. Healthcare providers also described how services may differ for boys in comparison with adult men, and several healthcare providers reported having previously provided services to boy victims/survivors of sexual violence. Consequently, some retrospective analysis of healthcare provision for boys is provided.

Healthcare providers did articulate barriers that boy victims/survivors of violence face in accessing healthcare services, including lack of knowledge of how to access a facility. However, healthcare providers appeared to lack awareness of the different needs of adults and children, and an understanding of how the evolving capacities of the child should be integrated into healthcare response. This may be due to most of the healthcare providers interviewed never having provided services to male victims/survivors of sexual violence, whether boys or adults. However, lack of understanding of or capacity to implement an approach that recognises the evolving capacities of the child was also found among healthcare providers who reported having provided services to girl victims/survivors of sexual violence, suggesting that there is a wider gap in this area.

More broadly, the research identifies other gaps in the provision of healthcare services to male victims/ survivors of sexual violence. Healthcare providers emphasized, for example, the unavailability of psychosocial services for victims/survivors of violence, and the lack of capacity of psychosocial counsellors to deliver services specifically to male victims/survivors of sexual violence.

One of the most important healthcare needs of male victims/survivors of sexual violence is to be treated with no judgement, blame or stigma. Victims/survivors also strongly emphasised the importance of confidentiality and the need to trust that a healthcare provider would not disclose their case to family or community members and, importantly, judicial actors, without their consent. Healthcare providers also emphasised the importance of these principles of care; however, it is unclear the extent to which they are implemented in practice. The research findings suggest that some healthcare providers may reproduce blame or stigma when male victims/survivors of sexual violence engage in sex work or if they identify as having diverse SOGIESC.

Further, the research points towards a possible gap in healthcare providers’ recognition of male victims/ survivors with diverse SOGIESC as a vulnerable group in need of services, or as legitimate victims/survivors of sexual violence. This lack of recognition may be due to assumptions that male victims/survivors with diverse SOGIESC who access health facilities for sexual violence have in fact consented to sexual acts and, thus, that these cases should be classed as sodomy, which is illegal under the Afghan Penal Code. It is unclear from the research what kinds of legal provisions healthcare providers are required to abide by with regards to male victims/survivors of sexual violence, including respect for confidentiality and rights to instigate the criminal justice process or not. Although the GBV Treatment Protocol articulates legal provisions for female survivors, the protocol does not articulate the rights of male victims/survivors of sexual violence.

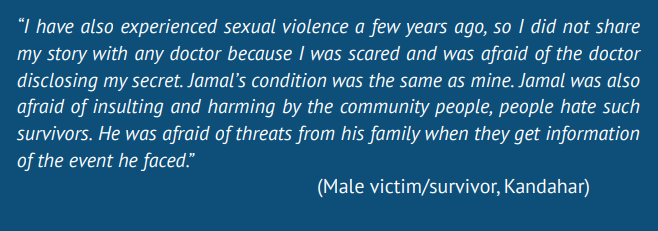

Concerns about stigma and shame feed into victim/survivors’ fears of disclosure of sexual violence to healthcare providers, and subsequent fears that they may be punished or experience further violence from perpetrators or even families if healthcare providers breach confidentiality and share their cases with others, including judicial actors. Victims/survivors also reported fears of being raped or sexually abused by healthcare providers and suggested that male victims/survivors with diverse SOGIESC may be at particular risk. These fears of confidentiality breaches, or of experiencing further sexual violence at the hands of a healthcare provider, feed into deep lack of trust in healthcare provision, which restricts victims/survivors from accessing a healthcare facility or disclosing their experience of sexual violence to a healthcare provider.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In light of the research findings, ASP and YHDO make the following recommendations based on the various levels and types of barriers that male victims/survivors face in accessing quality healthcare services. Although many of these recommendations are targeted towards the health sector, enhanced male victim/survivor access to healthcare services requires a multi-sectoral approach, and the recommendations reflect this need.

Recommendations to the Government of Afghanistan

Ministry of Public Health (MoPH)

- Raise awareness of the availability of healthcare services for male victims/survivors of sexual violence, including the types of healthcare facilities available that can meet their needs, and the protocols in place to protect their rights (e.g., confidentiality protocols, and mandatory reporting not being legally required). This can be done through targeted media campaigns, drawing on social media, television, radio and print media, and can also expand existing media disseminated by the MoPH, NGOs and civil society on healthcare provision to GBV victims/survivors.

- This recommendation is contingent on a greater understanding of the extent to which both government and non-government run healthcare facilities have the necessary protocols and services in place for male victims/survivors; to this end, a comprehensive mapping should be conducted.

- Develop specialised services for male victims/survivors of sexual violence, including boys, within public health facilities.

- This could involve expanding existing services targeted towards women and girls, such as Family Protection Centres (FPCs), and increasing the human resource and technical capacity of healthcare providers in these facilities to provide services to men and boys, including specialized social workers and counsellors, particularly for boys.

- Specialised services could also involve opening sections of regional and provincial hospitals that are resourced to provide services to male victims/survivors of sexual violence.

- Men and boys, particularly the latter, may be uncomfortable sharing their experiences with male healthcare providers given their experiences of abuse. Consequently, any specialised services should include both female and male healthcare providers and focal points and men and boys should be given the choice of the gender of the healthcare provider they consult with.

- Male survivors may fear for their own safety within a healthcare facility, including being emotionally mistreated, or experiencing inappropriate touching or unwanted sexual advances. Healthcare facilities should implement safeguarding policies that allow all victims/survivors to report any breaches of safety, with corresponding systems for independent follow up to and investigation of reports, and guarantees that victims/survivors will not be punished for reporting safety breaches. Victims/survivors should be made aware of safeguarding policies when accessing a healthcare facility and staff should be briefed and oriented on safeguarding policies and made aware of the repercussions if they do not comply.

- Conduct specialised training with healthcare providers on knowledge, attitudes and healthcare practices related to male victims/survivors of sexual violence.

- Ensure that the training challenges identified myths about the causes of sexual violence against men and boys and justifications for the actions of perpetrators. Healthcare provider misconceptions about the drivers of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV), and that armed perpetrators rape men and boys due to lack of education rather than weak rule of law and subsequent impunity, should also be addressed in training.

- Ensure that the training addresses how to enhance victim/survivor feelings of safety, including: treating the survivor with respect and empathy and not using any humiliating language; always asking for the consent of the survivor before physical examination, including of parts of the body associated with the sexual violence, and explaining at all times what the physical examination entails and how it will be performed; and giving the survivor the choice of having another person present during the medical consultation.

- Ensure that the training addresses healthcare provider capacity gaps identified in the research, including providing survivor-centred care to male victims/survivors at high risk of violence, such as those who engage in sex work or those with diverse SOGIESC.

- Ensure that the training addresses the evolving capacities of the child and how to integrate knowledge of these capacities into provision of care for child victims/survivors of sexual violence, including boys.

- Train and support CHWs to implement survivor-centred care when providing support to victims/survivors and referring them or facilitating their access to static healthcare services.

Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (MoLSA)

- Develop and implement reunification and reintegration programmes to facilitate male victims/ survivors to return safely to their families and communities.

- Strengthen the provision of livelihood support for male victims/survivors of sexual violence, both to ensure they have sufficient economic capital to access quality healthcare services, and to assist them to exit situations of sexual exploitation and abuse and to draw from alternative livelihoods options.

- Although healthcare providers and the MoPH are not well placed to support victim/survivors’ enhanced livelihoods, advocacy with other government bodies, particularly the MoLSA and NGOs supporting livelihoods of GBV victims/survivors, should be conducted and livelihoods support should be expanded to include male victims/survivors.

- Livelihoods programmes for male victims/survivors could involve family-level activities, both to enhance livelihoods at the household level and support efforts for reunification and reintegration of victims/survivors into their families and communities (see recommendation six).

Ministry of Education (MoE)

- Children’s lack of knowledge about their bodies, including their sexual organs and how to recognise inappropriate (sexual) attention or touching is an individual barrier, but one that requires interventions at the structural and community levels.

- Raise children’s (both boys and girls) knowledge and awareness of the risks of sexual violence by providing age-, culturally- and Islamic-appropriate Family Life Education (FLE). Although efforts to do this are underway, further advocacy is needed with the MoE to ensure that FLE materials are included in the national curriculum.

- Raise awareness in communities and families about the importance and acceptability of FLE, for example through targeted media campaigns and dissemination of information through community events, including through mosques.

Ministry of Justice

- Stronger measures must be put in place to ensure rule of law and accountability for all forms of sexual violence against men and boys, including CRSV. The revised Penal Code, including provisions relating to the banning of bacha bazi and all forms of child exploitation and abuse, should be widely disseminated in accessible formats. Recipients must include all national and local government officials, members of the judiciary and the Attorney General’s Office, the state security forces, community and religious leaders, teachers and others in positions of authority or influence. An effective and comprehensive victim and witness programme must be set up to enable survivors of sexual violence to safely report their case and pursue justice.

Recommendations to National Organisations

Health Sector NGOs

- Given that stigmatisation by family and community members, and subsequent threats of violence and abuse, are strong barriers to male victims/survivors accessing healthcare services, awareness-raising activities should be implemented at the community level.

- Train and support community level actors, including CHWs, community and religious leaders, and members of community health councils, to raise awareness of sexual violence against men and boys, reduce stigma against victims/survivors and support them to access healthcare services. Awareness raising, training and support must involve content on the importance of treating victims/survivors as victims rather than offenders.

- Given that male victims/survivors of sexual violence may be internalising victim-blaming discourses, work closely with them to reduce self-blame for the sexual violence they have experienced, and raise awareness of, and challenge, internalised stigma directed onto other male victims/survivors.

- Psychosocial counsellors are important actors in supporting this process of reducing self-blame and challenging the internalisation of stigma, and their capacity should be built to facilitate this process.

Recommendations to International Multi-Lateral Agencies

World Health Organization

- Update the GBV Treatment Protocol, or include an annex, with specific content on the needs of male victims/survivors of sexual violence, including boys and adult men and those with diverse SOGIESC. The updated protocol should aim to fill gaps in healthcare provider knowledge, attitudes and practices identified in this report, including those articulated in recommendation four.

- Ensure that the updated GBV Treatment Protocol or annex clearly articulates the legal rights of male victims/survivors of sexual violence, including boys and adult men.

- Facilitate the roll out of the GBV Treatment Protocol to private health facilities, including training of healthcare providers as outlined in recommendation four.

Recommendations to Donors

- Fund the development and implementation of standalone, specialised healthcare facilities for male victims/survivors of sexual violence most at risk (including those with diverse SOGIESC) such as the ones operationalized by YHDO.

- Fund health sector programmes targeting male victims/survivors of sexual violence that make linkages with other sectors, to ensure that the multiple and cumulative barriers facing male victims/survivors, including health, protection, livelihoods and justice barriers, are addressed.

INTRODUCTION

All Survivors Project (ASP) is an international non-governmental organisation (NGO) that supports global efforts to eradicate conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) and strengthen national and international responses to it through research and action on CRSV against men and boys, including those with diverse sexual orientation, gender identity and /or expression and sex characteristics (SOGIESC), as well as other people with diverse SOGIESC. Since 2018, ASP has been working in Afghanistan with its partner Youth Health and Development Organization (YHDO) on research and advocacy related to CRSV against men and boys.

In 2020, ASP was awarded a grant to conduct research with YHDO on healthcare services and responses for male victims/survivors of sexual violence in Afghanistan. This forms parts of ASP’s wider work in Afghanistan to advocate for enhanced justice, legal, protection, livelihoods, health and psychosocial responses for male victims/survivors. Although ASP’s mandate focuses on CRSV against male victims/survivors, the research conducted extends to all forms of sexual violence against men and boys, including conflict-related and nonconflict-related sexual violence. This recognises that an enhanced health sector response in Afghanistan is required for all male victims/survivors.

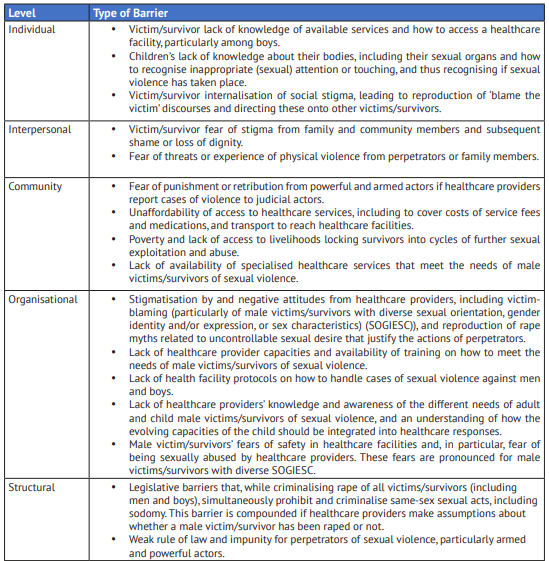

This report presents the key findings of the research and the recommendations made to the health sector, which will be used to support the development of a capacity-building tool for healthcare providers delivering services to male victims/survivors of sexual violence in Afghanistan. Throughout this report, a number of key terminologies are used and these are defined in Box 1. In line with ASP’s broader work, the report refers to male ‘victims/survivors’ of sexual violence, unless drawing from specific frameworks that use the term ‘survivor’ (such as the GBV Treatment Protocol for Healthcare Providers in Afghanistan). This framing recognises that not all men and boys who have experienced sexual violence view themselves as ‘having survived’ the abuse, and some may feel that they continue to be victimised. The term ‘victim/survivor’ acknowledges that people who have experienced sexual violence may identify themselves as a victim or as a survivor and that each individual has the right to choose the most appropriate language to express their individual experience.

Background

Gender-Based Violence in Afghanistan

Despite many gains made towards empowering Afghan women and girls in the last two decades, Afghanistan is still characterised by gender inequality, and women and girls experience widespread discrimination and abuses of human rights, including high levels of GBV. According to the Afghanistan Demographic and Health Survey conducted in 2015, 56% of ever-married women aged 15-49 had experienced physical, emotional or sexual intimate partner violence and this figure was as high as 92% in some provinces.[1] ‘Honour killing’ of women and girls is also practiced in Afghanistan, with 243 cases of ‘honour killings’ registered by the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission between March 2011 and April 2013, with perpetrators predominantly identified as husbands or other male relatives.[2] Many ‘honour killings’ are reported to occur in response to suspicion of women committing or attempting to commit zina (sex out of wedlock, including adultery), with women often being accused of zina after experiencing rape or other forms of sexual violence.[3]

Although women and girls in Afghanistan are extremely vulnerable to violence, much less is known about the prevalence of violence against men and boys, particularly sexual violence. The Child Protection Action Network (CPAN) received reports of 108 cases of rape and sexual abuse against children in 2012, with boys comprising slightly less than half of these cases. In 2011, a slightly higher proportion of boys than girls reported sexual abuse or rape to CPAN.[4] However, it is unknown who the perpetrators were (i.e., parties to the conflict or other perpetrators) and thus whether these cases constituted CRSV.

The literature suggests that sexual violence against boys in Afghanistan often occurs in a conflict context, with government and anti-government armed actors being key perpetrators. In reports compiled from UN and other credible sources on CRSV in Afghanistan,[5] there is evidence of multiple cases of sexual violence against boys perpetrated by Afghan security forces and anti-government groups, including sexual abuse of boys through the practice of bacha bazi. According to the Law on Protection of Child Rights, bacha bazi, meaning ‘boy for play’, involves dressing male children in female clothing and keeping them for sexual pleasure and/or dancing or singing in public or private parties, and often involves rape, sexual touching, pornography or other forms of sexual violence.[6]

Sexual abuse of boys and young men occurs in other circumstances, including in education settings. A study on violence against children in schools found very high levels of sexual abuse against boys, with teachers and older boys reported to be the main perpetrators of rape of younger boys.[7] Similar findings were found in a more recent study that revealed widespread perceptions among boys that teachers and older students frequently perpetrated sexual violence against boys in school settings.[8] In recent months, allegations of sexual abuse of boys in schools in Logar Province have drawn attention to the vulnerability of boys to abuse in education settings.[9]

The evidence suggests that boys who experience sexual violence may be vulnerable to wrongful incarceration after being raped or sexually abused, often on charges of ‘moral crimes’ including pederasty or zina (sex outside of wedlock). An assessment by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime published in 2008 found that 14% of boys in detention had been charged with homosexual behaviour, with boys as young as 11 years old being charged with pederasty despite being victims of rape or other types of sexual violence perpetrated by older men.[10] Men and boys with diverse SOGIESC may be at particular risk of experiencing sexual abuse. In an assessment of adolescent experiences of sexual exploitation and abuse among men who have sex with men (MSM) in three provinces (Kabul, Kandahar and Balkh), 16 out of 36 adolescent MSM in Juvenile Rehabilitation Centres reported having had some experience of sexual assault with another male, whether as the victim/ survivor or perpetrator. [11] Vulnerability to abuse also occurs outside of these settings. A survey of MSM in Afghanistan found that 40% of those sampled reported having been raped by another man.[12] Reports of sexual violence were less common in another sample of MSM, 25% of whom reported having been forced to have sex in their sexual debut. However, 63% reported having negative feelings about this experience.

Health Sector Response

Afghanistan’s healthcare system is structured around the Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS) and the Essential Package of Hospital Services (EPHS), which comprise government health services and facilities predominantly run by NGOs. Under the BPHS and EPHS, healthcare services operate at three main levels. The first comprises community level services, delivered through health posts that are catchment areas for the outreach work of male and female trained volunteers referred to as community health workers (CHWs), or small static health facilities including health sub-centres (HSCs) and basic health centres (BHCs).[13] The second comprises district-level static health facilities located in larger communities or in district centres, including comprehensive health centres (CHCs) and district hospitals. The third level comprises provincial and regional hospitals.[14] The levels range from basic to more complete healthcare services, with an upward referral system under which more complex cases are referred to higher levels where there are larger numbers of healthcare staff, services and resources. Static facilities are supported by mobile health teams which perform outreach work in communities and provide additional opportunities for linking communities with the upwards referral structure. In addition to these different types of static and mobile health services overseen by the MoPH, some health facilities in Afghanistan are also run privately.

A range of services have also been developed specifically to address the health care needs of victims/survivors of GBV, although these are largely directed towards women and girls. Thirty-seven Family Protection Centres (FPCs) have been established in 26 provinces by the MoPH with support from UNFPA (the UN Population Fund) and implementing partners, and form part of a wider multi-sector response to a GBV programme that provides health, police and justice services for victims/survivors, with FPCs providing the primary entry point. FPCs are located in government provincial and regional hospitals to ensure their sustainability within the national health system, and provide support to victims/survivors, including basic health services, medical support, psychosocial counselling, legal support, help in collecting evidence and providing referrals to other services. Health focal points are available at the district level and refer GBV cases to the FPCs or other services, and FPCs conduct quarterly based coordination meetings with the health focal points. The MoPH, with the support of UNFPA, also has Women Friendly Health Spaces to identify GBV cases, provide support to victims/survivors and refer them to FPCs or other services. Despite these mechanisms to assist access to FPCs and other services, FPCs may not be accessible for all victims/survivors, particularly those who live in more remote locations. Consequently, some NGOs working in humanitarian response now send mobile outreach teams (comprising a psychosocial counselor, a community mobiliser and midwife) to visit communities and provide GBV services and referrals.[15] Although there has previously been resistance in Afghanistan to expanding CHW roles to respond to GBV,[16] it is recognised that, globally, CHWs are a key entry point to GBV health services for community members who cannot access formal services.[17] It is unknown, however, the extent to which CHWs in Afghanistan fulfill these functions.

Several resources have been developed to facilitate higher quality of health care provision for victims/ survivors of GBV, although, much like GBV services, these resources are largely directed towards women and girls. These include: a training manual for health professionals on a trauma-sensitive approach to care for victims/survivors of GBV in Afghanistan, developed in 2011 by medica mondiale and Medica Afghanistan; Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for Healthcare Sector Response to GBV, developed in 2013 by the MoPH and UNFPA; the GBV Treatment Protocol for Healthcare Providers in Afghanistan developed in 2014 by the MoPH, WHO and UN Women (GBV Treatment Protocol); and a comprehensive training package developed by WHO and UNFPA to train healthcare providers to use the GBV Treatment Protocol.

The GBV Treatment Protocol contains comprehensive information and guidance on a range of topics, including: legal frameworks and requirements, patient flow, confidentiality, documentation and reporting, survivor-centred care, identifying and responding to patient disclosures of GBV, and different types of care for victims/survivors. The Protocol is intended to provide guidance on healthcare response to all GBV victims/ survivors; however, although it notes that men and boys, particularly adolescent boys, can experience sexual exploitation and violence, the Protocol emphasizes that women and girls are disproportionately affected by GBV and the Protocol is largely targeted towards them. There are some sections of the Protocol that explicitly refer to the provision of services for men and boys; however, there are also a number of gaps in this regard, as articulated in this report.[18]

Despite the development of the BPHS and EPHS, and specialised services and resources for victims/survivors of GBV, there are persistent barriers to female victims/survivors accessing healthcare services in Afghanistan and these are well documented in the literature.[19] However, very little is known about the barriers that men and boys face accessing GBV services following experiences of sexual violence. An MoPH psychosocial counselling training package on GBV suggests that male victims/survivors of rape are much less likely to report the incident or seek health care due to feelings of embarrassment.[20] The GBV Treatment Protocol also has a brief section on men, which notes that male victims/survivors of GBV are unlikely to seek medical attention unless they have had severe injuries, in part due to the stigma and cultural sensitivities around sexual violence against men. The Protocol also notes that men presenting to healthcare providers after experiencing rape may be concerned about their masculinity, sexuality, inability to prevent the assault, or the opinions of others who may think they are homosexual.

Research on Male Victims/Survivors of Sexual Violence

In order to address the large gaps in knowledge about male victims/survivors of sexual violence in Afghanistan and the barriers they face accessing quality healthcare provision, ASP and YHDO conducted research in 2020. The objectives of the research were to:

- Understand the healthcare experiences and needs of male victims/survivors of sexual violence and the barriers to their access to quality healthcare services.

- Understand the practices of healthcare providers in relation to supporting male victims/survivors of sexual violence and the barriers they face in providing quality healthcare services to them.

- Understand what a survivor-centred approach to healthcare provision means, and how it is applied in Afghanistan, with regards to male victims/survivors.

- Develop a set of recommendations for enhanced survivor-centred healthcare services for male victims survivors of sexual violence that will be used to develop a tool for the health sector.

OVERVIEW OF METHODOLOGY

This section provides an overview of the methodology and methods employed for the research: a full description is included in Annex A.

The research was conducted in three provinces: Kabul, Balkh and Kandahar. These provinces were not selected on the basis of estimates of the prevalence of sexual violence against men and boys.[21] Rather, they were selected in order to capture data from three geographical regions of the country (central, northern and southern) and also because of YHDO’s presence in these regions. Data collection was conducted between August and November 2020.

The overall research approach was qualitative, with four key methods employed:

- Desk review: A desk review was conducted, including literature on sexual violence against men and boys and the health sector response, with a focus on evidence from Afghanistan. A list of selected documents is provided at the end of this report, with URLs where available.

- Stakeholder mapping: A stakeholder mapping was conducted to identify existing systems of healthcare response that include coverage of male victims/survivors, predominantly through a desk review of online documents.

- Key informant interviews with stakeholders: From the stakeholder mapping, a selection of stakeholders were invited to participate in key informant interviews (KIIs). Ten interviews were conducted with a range of individuals, including government stakeholders, and staff from national and international NGOs and UN agencies.

- In-depth interviews: In-depth interviews (IDIs) were conducted with 27 male victims/survivors of sexual violence, 44 healthcare providers working in different types of static health care facilities, and 26 community health workers, with a total of 97 IDIs conducted.

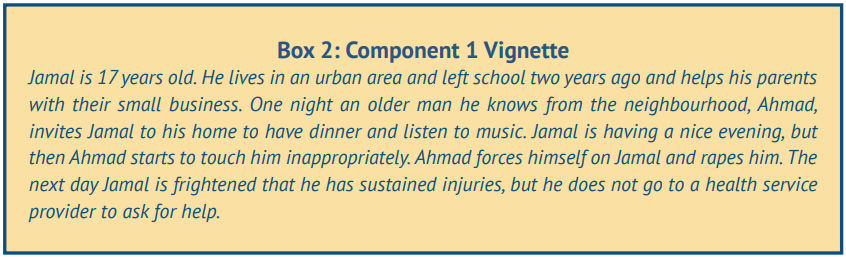

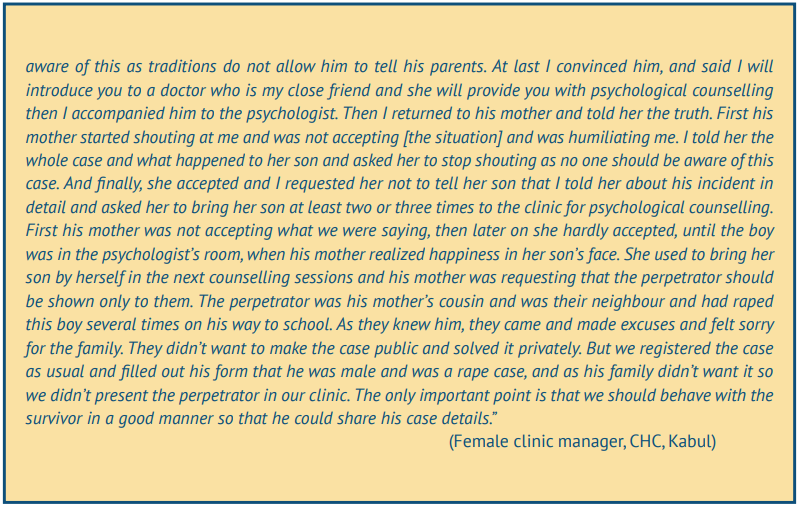

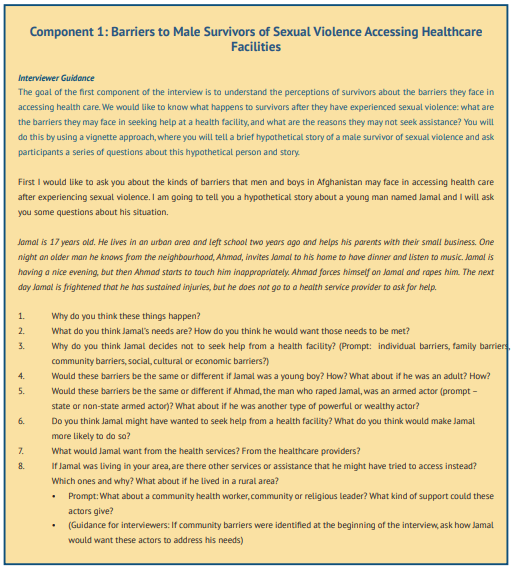

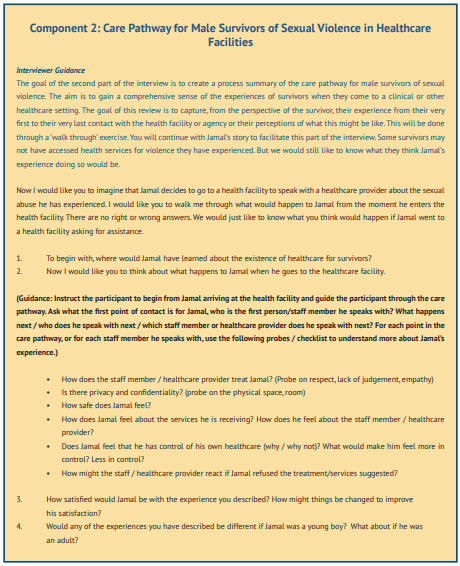

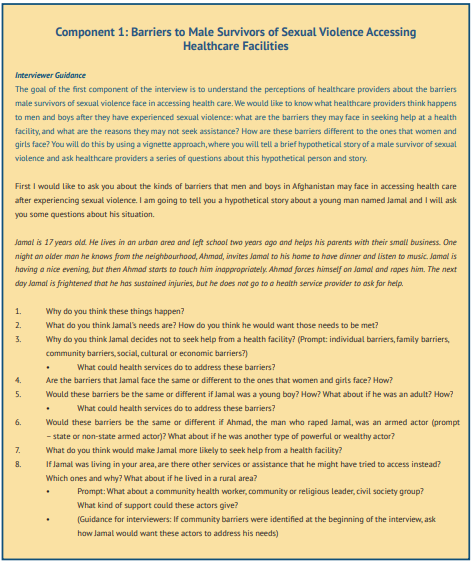

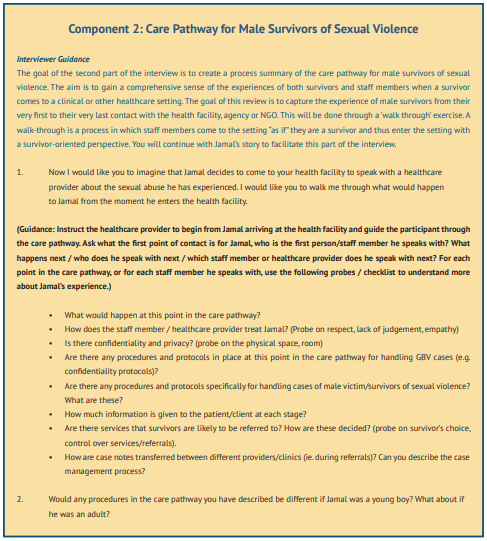

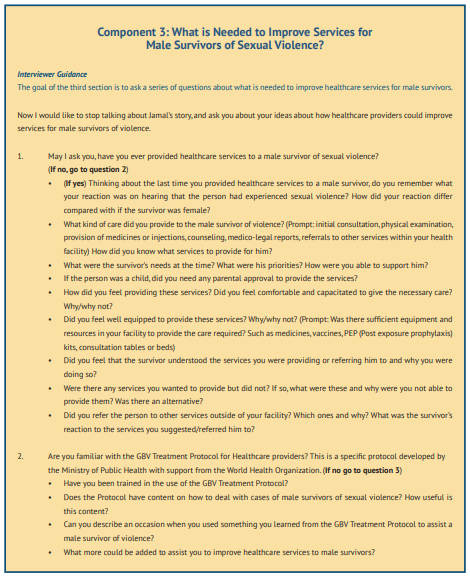

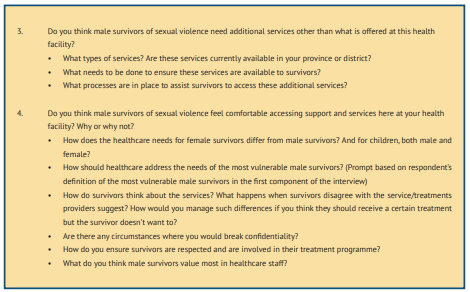

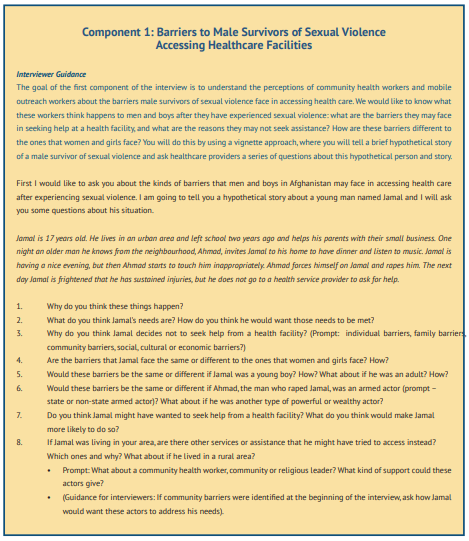

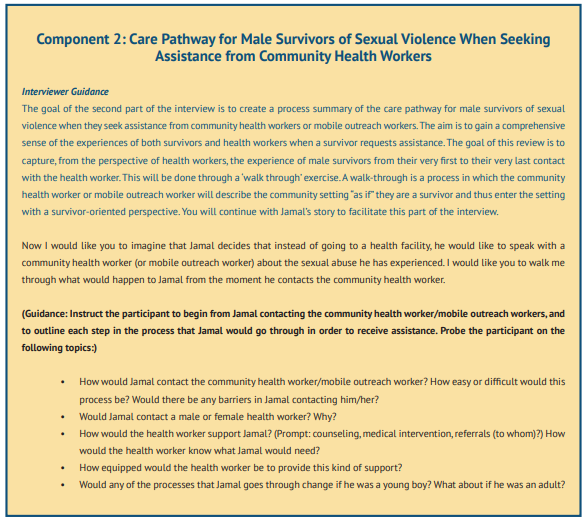

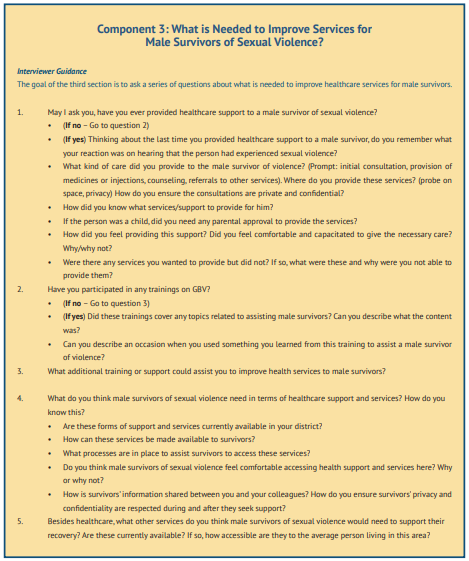

IDIs were based on a storytelling approach in which a vignette/story of a male victim/survivor of sexual violence was used to prompt storytelling and discussion whereby different types of participant were asked to discuss the story through the eyes of the victim/survivor. Three different qualitative tools were developed for each type of participant (male victims/survivors, healthcare providers, and community health workers), and all three were harmonised to draw from the same approach. All three tools were divided into three components:

- A vignette of a hypothetical scenario involving sexual violence perpetrated against a 17-year-old boy who does not access health services (see Box 2) and questions or probes about why he does not want to do so and the barriers that he might face if he does.

- A continuation of the vignette to facilitate a walk through a healthcare pathway to explore what occurs when a victim/survivor accesses services at a healthcare facility or through a community health worker.

- A series of questions about participants’ own experiences accessing healthcare after experiencing sexual violence (for victims/survivors) or delivering healthcare services (healthcare providers and community health workers) and what is needed to improve healthcare response for male victims/ survivors.

These three components are described more fully in Annex A, and the tools are included in Annex B.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all data collection was done remotely through telephone interviews. The research team had concerns about how to ensure the confidentiality and privacy of male victims/survivors when engaging in telephone interviews. Consequently, in order to mitigate risks, a hybrid approach was employed whereby victims/survivors were supported to access a YHDO office where they were provided with a safe, private and COVID-19 sterilised space with the necessary technology to participate in an interview facilitated remotely.

The research was conducted in line with an ethical, safe and survivor-centred approach.

- Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the MoPH in Afghanistan.

- No male victims/survivors under the age of 18 were sampled for the research.

- All participants were required to provide informed consent before participating in interviews.

- Confidentiality for participants was ensured by de-identifying transcripts and removing names, names of healthcare facilities or organisations and district names from the report.

- In order to handle victim/survivors’ possible distress and re-traumatization, YHDO had counsellors available to provide services.

- The research team participated in ethics and safety training, including on ensuring privacy and confidentiality, obtaining informed consent without coercion, respecting the withdrawal of consent at any time, ensuring respect for victims/survivors at all times, recognising signs of distress and handling disclosures of violence.

The research team faced a number of challenges implementing the research, leading to some limitations. See Annex A for a more extensive discussion of challenges and limitations, with the main ones listed below.

- Only seven male victims/survivors (one quarter of those interviewed) reported having accessed non-YHDO healthcare facilities for sexual violence they had experienced in the past. Further, only nine healthcare providers (one fifth of those interviewed) reported having provided services to male victims/survivors of sexual violence. This challenge was expected and difficult to avoid given the substantial barriers male victims/survivors face accessing healthcare services and was one of the reasons for using a hypothetical vignette approach in the interview tools. Consequently, much of the data is based on perceptions or, in the case of victims/survivors, what they had heard from other victims/survivors, rather than on their own direct personal experience.

- Only one CHW reported having provided support to male victims/survivors. Although the CHW data was useful insofar as CHWs are widely recognised as a possible entry point to male victim/survivors’ access to healthcare facilities through referrals, CHWs had little awareness or knowledge about male victims/survivors of sexual violence or their needs.

- Given that all victims/survivors interviewed were adults, there is an important gap in the research on the experiences of boys. The research team was able to analyse some data retrospectively where adult men disclosed that they had experienced sexual violence at a young age. Further, of the nine cases in which healthcare providers reported that they had provided services to male victims/survivors in the past, five referred to providing services to boys, also allowing additional learning about healthcare response to boy victims/survivors of sexual violence. However, the lack of direct data collected on child and adolescent boy experiences of accessing healthcare services is a gap that is important to address in future research.

RESULTS

Barriers to Male Victims/Survivors of Sexual Violence Accessing Healthcare Services

The research has identified a number of barriers that prevent male victims/survivors of sexual violence from accessing healthcare services. Following a social ecological model of public health,[22] this section presents these barriers according to five different levels: (1) individual barriers, (2) interpersonal barriers (3) community-level barriers, (4) organisational barriers and (5) structural barriers. It should be noted that these barriers do not operate in isolation and male victims/survivors face multiple, mutually reinforcing barriers, making access to healthcare services extremely challenging.

Lack of Knowledge or Awareness

At the individual level, lack of knowledge or awareness emerged as a barrier to male victim/survivors’ access to healthcare. This barrier was described in different ways by male victims/survivors and healthcare providers but in both groups age was implicated, and this barrier was framed as one particularly facing younger boys.

Male victims/survivors suggested that lack of awareness of how to access a healthcare facility, including lack of knowledge about their location and what services are available, was a key barrier. They emphasized that younger boys would be unlikely to understand how to access a healthcare facility or to have the autonomy to do so, and victims/survivors who had first experienced sexual abuse as a child noted being unaware of how to access healthcare facilities. In contrast, older adolescent boys and adult men were perceived to have greater awareness of available services and the mobility to reach them. Healthcare providers also expressed awareness that boys were likely to have limited knowledge of how to access a facility or that these services existed and were reliant on caregivers to facilitate access.

Healthcare providers raised the issue of children’s lack of knowledge about their bodies and inappropriate sexual touching, and that children may not understand that they have been sexually abused. Approximately a quarter of healthcare providers interviewed for the research raised the lack of appropriate sex and relationship education in Afghanistan as a key driver of sexual violence against boys. In cases where this issue was raised, healthcare providers emphasized that both boys and girls needed to learn how to protect themselves from sexual violence by acquiring information about their bodies, including their sexual organs and how to recognise inappropriate (sexual) attention or touching. In most cases, families were perceived to be the most appropriate actors to deliver this education to their children. However, a small number of healthcare providers (three) emphasized that Afghanistan’s education system was a more appropriate system through which to deliver sex and relationship education. In recent years, academics and international organisations working in Afghanistan have advocated for the inclusion of comprehensive sexuality education, often referred to as Family Life Education (FLE), to be included in the national curriculum.[23] Although the MoPH with support from UNFPA has developed and handed over a series of FLE materials to the MoE[24], these are yet to be integrated into the national curriculum.

Despite participants suggesting that adult men were more likely to know how to access a healthcare facility, the results of the research suggest that victims/survivors may lack knowledge of the type and quality of care they will receive. There was significant dissonance between healthcare provider descriptions of the care they would provide to a male victim/survivor, and the treatment that male victims/survivors expect to receive (see further details in the sections of this report on healthcare services for male victims/survivors of sexual violence and the needs of male victims/survivors). Although this may be due in part to some persisting gaps in the capacity of healthcare providers to deliver services to male victims/survivors, it is also possible that victims/survivors are unaware of existing protocols (e.g., confidentiality protocols) and how the health sector has grown more generally in relation to GBV response (for instance, with the roll out of the GBV Treatment Protocol and the establishment of FPCs).

Social Stigma

Social stigma has been found to be a significant barrier to male victim/survivors’ help-seeking in a number of different country contexts, including in conflict and humanitarian settings. Several studies have emphasized male victim/survivors’ fears of social stigma from family and community members and the emotional abuse and mistreatment that they would experience if their victimization is known to others in their community or family. [25]

In data collected for this study, almost all the male victims/survivors interviewed referred to social stigma and subsequent shame or loss of dignity as the most important barrier they faced in seeking help from a healthcare facility. A common theme was the poor treatment of victims/survivors by community members, who were reported to tease, taunt and humiliate victims/survivors due the violence they had experienced. Victims/survivors described many negative impacts of this poor treatment from community members, including feelings of rejection and social isolation and the subsequent negative impacts on mental health, in some cases leading to suicidal thoughts. Victims/survivors noted that stigmatising attitudes and behaviours from community members, including peers, may lead them to drop out of school or leave their communities to escape mistreatment. Victims/survivors also described the negative impact that stigma has on the honour and reputation of their families, and suggested that preserving their families’ dignity was a key reason for decisions not to seek help. Victims/survivors suggested that families may also need to relocate to a different community to escape stigma and shame.

Victim/survivors’ perceptions of sources of stigma are closely linked to ‘blame the victim’ discourses whereby the source of stigma is perceived to be the assumption that victims/survivors are responsible for the violence they experienced. Just over 50% of the male victims/survivors and approximately 15% of the healthcare providers and CHWs sampled for the research reproduced a ‘blame the victim’ discourse. Victim blaming is a common community response to all victims/survivors of sexual violence, including male and female victims/survivors, and is often linked to preserving the power and privilege of perpetrators and social norms that justify violence.

The majority of participants who reproduced a ‘blame the victim’ discourse (approximately three quarters of male victims/survivors and healthcare providers, and all CHWs) suggested that victims/survivors should have ‘known better’ and were to blame for making a decision to enter a situation perceived to be risky. While participants often recognised that victims/survivors may have been deceived by perpetrators, victims/ survivors were still perceived to be at fault for the situation arising at all.

The second type of ‘blame the victim’ discourse was that if a risky situation could not be avoided, then it was the responsibility of the victim/survivor to defend himself or escape the situation. This discourse was only used by four male victims/survivors.

The third type of ‘blame the victim’ discourse was that the victim/survivor must have wanted sexual engagement and so the sexual act would have been consensual. Only three victims/survivors and one healthcare provider reproduced this type of discourse, which was linked to the previous two discourses insofar as victims/ survivors were presumed to have consented to sexual engagement if they (a) entered a situation assumed to be risky and/or (b) did not attempt to run away or defend themselves (or were not successful in doing so). This ‘blame the victim’ discourse was linked to the perceptions of victim/survivors’ SOGIESC. Where the victim/survivor in the hypothetical vignette was positioned as having a diverse SOGIESC, including being gay or transgender, there were assumptions that he may have welcomed the sexual violence.

These three ‘blame the victim’ discourses were largely targeted toward adult male victims/survivors, suggesting that age is an important factor in how people perceive the role of men and boys in negotiating risk of sexual violence, and the subsequent stigmatisation of victims/survivors if they are unable to negotiate this risk. Younger boys are perceived to suffer less stigma due to assumptions that they are less able to understand the consequences of being in situations that could heighten risk of sexual violence, are unable to defend themselves, have no sexual desire and are unable to consent to sexual relations. In contrast, adult men are presumed to be able to avoid, or defend themselves from, sexual violence and are thus blamed for the violence they experience. According to victims/survivors, in general, stigma is less pronounced for younger boys, and families are more likely to facilitate boys’ access to a healthcare facility. However, as the age of boys increases, families are perceived to be less likely to support their access to healthcare due to greater stigma and shame.

It is important to note that ‘blame the victim’ discourses were reproduced more by victims/survivors than by healthcare providers or CHWs. There are a number of reasons why this might be the case. It is possible that male victims/survivors direct stigma and blame onto other male victims/survivors as they have internalized the stigma and blame they have received from others. For instance, there is evidence in other settings that male victims/survivors may internalize negative attitudes, beliefs and stigma, although this usually occurs through self-blame rather than blaming other men or boys.[26] It is also possible that male victim/survivors’ past experiences of sexual violence have led to deep feelings of suspicion of other men, including those who may be perpetrators, which is a documented impact of sexual violence on some men and boys.[27] This was particularly evident in victim/survivors’ reproduction of the first type of ‘blame the victim’ discourse, whereby they stressed that all men and boys should be discerning about accepting social invitations from other men, particularly at night.

Although fewer healthcare providers and CHWs reproduced ‘blame the victim’ discourses, it is interesting to note that those who did were all male. This could be due to a bias in the sample given that there were more male than female healthcare providers and CHWs interviewed for the research. However, it is also possible that there is a gender dimension to discourses that stigmatise and blame men and boys, including among victims/survivors themselves. Research participants did not explicitly refer to masculinity or what it means to be a man in Afghan society. However, perceptions that men and boys are responsible for controlling their social environment and defending themselves from risk, including physically defending themselves, may point towards models of masculinities that male research participants in particular reproduce.

Threats of Violence and Abuse

Victim/survivors’ fears of experiencing emotional abuse, including being teased or taunted by community members, emerged as a significant barrier to their access to healthcare services. However, a number of victims/survivors also reported fears of experiencing threats of physical violence if they disclosed their experience to a healthcare provider.

When research participants referred to threats of physical violence against victims/survivors, they emphasized the risk of threats from perpetrators who might fear the disclosure of their identity to healthcare providers who may then refer the case to judicial actors. There were widespread perceptions that disclosing cases of violence to healthcare providers could create additional problems for victims/survivors if perpetrators of sexual violence retaliated against victims/survivors or their families. Victims/survivors from all three provinces stressed how threats from perpetrators would be more pronounced if they were armed actors or other types of powerful actors. Victims/survivors emphasized the greater threat of physical violence, including murder, to themselves and their families if perpetrators were armed. This may occur through verbal threats of violence to force victims/survivors to remain silent or direct acts of physical violence if a victim/ survivor’s case is reported to the judiciary via a healthcare facility. Several victims/survivors also suggested that perpetrators of sexual violence would not necessarily make physical threats, but may blackmail victims/ survivors and pressure them to stay silent; for instance, by threatening to show video or photographs of the rape to relatives or to post them on the internet or social media.

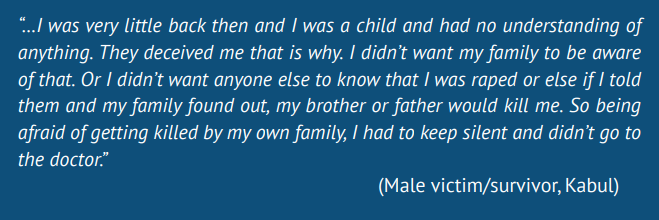

Despite concerns about perpetrators threatening victims/survivors being common, male victims/survivors of sexual violence frequently referred to physical threats from their own family members. A third of victims/ survivors interviewed for the research, particularly those in Kandahar and Kabul, suggested that families might beat or even kill victims/survivors if the family is perceived to be dishonoured or shamed. Several victims/survivors also referred to fears of family members throwing them out of the house or forcing them to leave their community.

Although the types of fears outlined above were common in male victim/survivors’ narratives, it is interesting to note that healthcare providers perceived threats of physical violence or murder in the name of ‘honour’ to be a problem faced mainly by female victims/survivors. Healthcare providers highlighted the importance of girls’ virginity in Afghan culture and the negative repercussions on women and girls if they are raped given they become less marriable, leading to perceptions of shame and dishonour in the family. However, there was less recognition that male victims/survivors might also be punished through violence, partly due to perceptions that the shame would be less given that men and boys would presumably be able to marry in the future.

Conflict

Almost all of the participants interviewed for the research recognised that perpetrators of sexual violence against men and boys, particularly bacha bazi, are often armed actors, including government and nongovernment armed actors and armed warlords. As noted in the previous section, victims/survivors emphasized how threats from perpetrators, including threats of physical violence and murder (both to themselves and their families), were particularly strong barriers to accessing healthcare services in cases where perpetrators were armed actors. These barriers were largely linked to concerns about cases being referred from healthcare facilities to judicial actors, and the subsequent risks that this would pose to survivors and their families if armed actors retaliated against them.

Despite overall recognition that perpetrators of sexual violence against men and boys are often armed actors, few research participants emphasized power in conflict as a driver of sexual violence against men and boys. Healthcare providers and CHWs in particular perceived armed actors to perpetrate sexual violence due to lack of education. Three quarters of healthcare providers and CHWs who referred to armed actors suggested that they were illiterate, had not received an appropriate Islamic education or were not sufficiently knowledgeable about national laws, international human rights laws or Sharia laws that prohibit sexual violence. These perceptions were accompanied by assumptions that if armed perpetrators were adequately educated, they would not perpetrate sexual violence against men and boys.

In the limited cases in which conflict drivers were more explicitly stated, research participants referred to conflict-driven displacement of boys putting them at risk of sexual violence, including where displacement led boys to join non-government armed groups. Other conflict drivers mentioned included the death of boys’ family members as a result of conflict, leading them to work to support their households, including in situations that put them at heightened risk of sexual violence (e.g., sex work or street work). Only a few participants (four healthcare providers), suggested that weak rule of law (rather than the educational level of perpetrators) was a key conflict driver of sexual violence against men and boys. These participants highlighted the impunity of powerful perpetrators and their connections with government officials (or in many cases perpetrators belonging to government entities) as being a more significant factor in CRSV.

Poverty and Economic Vulnerability

In Afghanistan, poverty is a recognised barrier to access to healthcare services more generally,[28] and a barrier that women and girl victims/survivors of GBV also face, including lack of funds to pay for transport (especially if living in remote and rural locations) or medical service fees.[29] The research suggests that male victims/survivors of sexual violence may also face economic barriers to accessing healthcare services. Just over three quarters of participants, particularly healthcare providers, emphasised economic barriers to access to healthcare services. There was some variation in perceptions of the types of economic barriers male victims/survivors might face. Most healthcare providers highlighted that services in government healthcare facilities under the BPHS and EPHS were free and that lack of money should not pose a significant economic barrier in this regard. Although victims/survivors also made reference to government facilities offering free services, several suggested that payment for government services was sometimes required. It is possible that some victims/survivors lack awareness of the free nature of primary health services captured under the BPHS and EPHS. However, it is also possible that they are referring to services that are not covered by the BPHS and EPHS.

Despite general recognition that victims/survivors could access free healthcare services in government facilities, both victim/survivors and healthcare providers cited economic problems associated with access to available government facilities. In particular, they highlighted how difficult it was for victims/survivors with poor socio-economic status living in rural or remote areas to pay for transport to access a healthcare facility at the district level or in the provincial centre. Victims/survivors noted this barrier more in relation to hypothetical scenarios involving other male victims/survivors rather than their own experiences, which is likely due to victims/survivors being sampled in urban settings where transport is more readily available. Nevertheless, victims/survivors reported other types of economic barriers, including lack of provision of medications, which those from poor families were unable to afford, despite BPHS facilities providing essential medications for patients. This suggests that victims/survivors may not have adequate information about the provision of services in government facilities.

References to lack of money for transportation and to purchase medicines were particularly common in Kandahar. In cases where victims/survivors recognised that government healthcare services were free, several suggested that the quality of services were poor and that victims/survivors were better off accessing private facilities, which are perceived to have better quality services, including stricter confidentiality. However, private facilities are perceived to be unaffordable for poorer families. One healthcare provider in a private facility referred to a charity section that delivered free services to patients who were poor, and there are some private facilities that have mechanisms in place to reduce costs for poor families; however, it is possible that male victims/survivors are unaware of these mechanisms for support.

Poverty and economic vulnerability were not only described as key barriers to healthcare access, but were also described as key drivers of sexual violence against men and boys. Research participants perceived sexual violence to occur when families failed to safeguard sons, and this failure was directly linked to poverty and economic vulnerability. A common way in which families, particularly parents, are perceived to have failed to safeguard male children is through perceptions that they have insufficient oversight of their children, with parents described as often too busy working to be aware of what their sons were doing. Another way that families are believed to have failed to safeguard sons is related to perceptions that poor families may increase the vulnerability of boys by putting them in situations of risk. In some cases, participants suggested that families might actively do so by encouraging or forcing them to participate in labour that might leave them vulnerable to participation in sex work or practices associated with sexual exploitation and abuse, including bacha bazi. However, the majority of research participants suggested that families were to blame in a more indirect way by forcing boys to drop out of school and/or participate in child labour, with street working boys perceived to be at particular risk of sexual violence.

Economic factors were not always depicted as the fault or responsibility of victim/survivors’ family members. Two male victims/survivors and one male CHW actively positioned perpetrators of bacha bazi as responsible for economically and sexually exploiting boys due to the poverty of their families. Some research participants (eight male victims/survivors, five healthcare providers and four CHWs), particularly in Kandahar, depicted male victims/survivors as more active agents seeking economic activity or independence. In most of these cases, research participants did not reproduce ‘blame the victim’ discourses but rather suggested that perpetrators deceived boys and men by preying on their economic needs and providing them with economic assistance.

Perpetrators’ exploitation of victim/survivors’ ‘weakness’ was a theme that emerged across a number of interviews; however, ‘weakness’ was not always defined in relation to economic need or poverty. Several victims/survivors referred to boys and men wanting or needing other forms of support that perpetrators might provide, including social networks or access to employment, or that perpetrators might entice boys with gifts, including mobile phones or clothes, or social status. The formation of these relationships was perceived to lock boys and men into economically dependent relationships with perpetrators that would inevitably be accompanied by or end in sexual violence.

Availability of Services

Only three research participants across the whole sample stated that lack of facilities was a barrier to male victims/survivors seeking healthcare services, and there were widespread perceptions among healthcare providers in particular that the BPHS was largely successful in reaching the population at the community level, including victims/survivors of violence. Nevertheless, there was widespread recognition that there was a lack of specialised services for this particular group. Male victims/survivors emphasized their preference for a healthcare facility that had specialised capacity to assist men and boys, and particularly a preference for private, non-public health facilities due to the barriers already noted, including perceptions that private healthcare facilities had higher quality care and better confidentiality procedures.

A number of healthcare providers suggested that GBV procedures and protocols would be easier to manage if healthcare facilities had a specific department for GBV cases, and both victims/survivors and healthcare providers suggested that facilities would benefit from having a section focused on delivery of services for men and boys who had experienced sexual violence. Few healthcare providers spoke about how such a department would function in a way that would protect the privacy of victims/survivors and avoid stigmatisation of those actively seeking services. One healthcare provider noted that any department tasked with providing services to victims/survivors of GBV, whether female or male, should not be visibly marked as such in order to respect confidentiality and privacy, which is in line with recommendations made in the GBV Treatment Protocol. However, one healthcare provider suggested that “the GBV services room should have a signboard to be visible for everyone without asking about it” and another suggested that such signboards were present in their own facility, suggesting that not all providers understand the implications of stigma for victims/ survivors and the harm of visibly labelling GBV services.

One stakeholder from a UN organisation suggested that specific health centres should be established to directly target ‘men with high-risk behaviours’ given they are from a particularly vulnerable group that experiences heightened stigma. Others suggested that existing healthcare facilities could be expanded to meet the needs of male victims/survivors. For instance, FPCs, which are typically located in provincial or regional hospitals, do serve the function of targeting services specifically to victims/survivors of GBV. However, there were some conflicting perspectives on the extent to which FPCs can or do provide support to male victims/survivors of sexual violence. One FPC focal point in Kandahar suggested that the FPC only provided services for women and girls, and that there were no parallel centres for men and boys. However, two stakeholders interviewed for the research, one from the MoPH and another from an NGO running an FPC in Kabul, stressed that the mandate of FPCs was to deliver services to any victim/survivor of GBV. Nevertheless, stakeholders emphasized that given FPC staff are all female, it is rare that male victims/survivors would approach an FPC seeking assistance and in almost all cases they would be boys (although men may also come to an FPC asking for assistance, they would be referred to other healthcare facilities with male staff). According to the stakeholder interview with an MoPH focal point, 70 cases of sexual violence against male victims/survivors were registered in FPCs between 2013 and 2020. An FPC focal point in Kabul also noted that they had received cases from male victims/survivors of sexual assault in the past, although not more recently in 2020. This focal point reported that the FPC referred male victims/survivors to YHDO and that the lack of male victims/survivors attending the FPC in 2020 could be because these men and boys in Kabul are now aware of YHDO services and seek them directly.

Stigma From and Negative Attitudes of Healthcare Providers

It is well documented in Afghanistan that a significant barrier to women and girl victims/survivors accessing health services is the negative and stigmatising attitudes that healthcare providers might direct towards them.[30] Although there is no data available on healthcare providers’ attitudes and behaviours towards male victims/survivors of sexual violence in Afghanistan, the global evidence suggests that negative attitudes of healthcare providers, including using humiliating, blaming and stigmatising language, are a significant barrier to victim/survivors’ healthcare access.[31]

The victims/survivors interviewed for this research also reported fear of stigma, blame and negative attitudes from healthcare providers as a barrier to accessing healthcare services. Victim/survivors’ concerns about being stigmatised and blamed by healthcare providers are mostly in line with the ‘blame the victim’ discourses, outlined previously: the victim/survivor should have ‘known better’; the victim/survivor must have developed inappropriate social engagements; the victim/survivor should have defended himself; or the victim/survivor must have wanted sexual engagement. In addition, two victims/survivors suggested that poor treatment from healthcare providers, including blame and judgement, may be due to concerns that stigma might somehow affect the facility and bring the ‘dignity’ of the facility into disrepute.

Victim/survivors’ fears of being blamed or judged by healthcare providers appear to be particularly pronounced among male victims/survivors with diverse SOGIESC. Victims/survivors referred to the specific visibility of those with diverse SOGIESC, and the verbal abuse that they would face if attempting to access a healthcare facility. For instance, one victim/survivor from Kabul described how the recognition of a transgender victim/ survivor’s gender expression as ‘different’ would be linked to abusive behaviour from multiple staff along the care pathway, and even before the victim/survivor reaches the healthcare facility.

This extract has a number of important implications. One is that stigmatising behaviour towards victims/ survivors begins well before they arrive at a healthcare facility. Further, although healthcare providers deemphasized the role or importance of guards or initial clinic focal points in providing services to victims/ survivors of violence, the fears of male victims/survivors with diverse SOGIESC illustrate how stigmatising treatment from initial clinic focal points can discourage victims/survivors from attempting to access a healthcare facility. Another implication is that regardless of how a victim/survivor with diverse SOGIESC is treated by a medical practitioner, by the time he reaches that point in the care pathway trust in care is likely to have diminished.