On 17th July, the UN Security Council will hold its Open Debate on Sexual Violence in Conflict which will present UN Member States with an opportunity to reflect on the steps necessary to address the current widespread impunity for conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV).

Despite repeated calls and commitments by the UN and Member States, justice still eludes the vast majority of victims of CRSV and prosecution remains rare. The report of the UN Secretary-General on conflict-related sexual violence notes with concern the “slow pace of justice and the absence of reparations” for survivors of sexual violence.[1] While impunity affects all survivors, men and boys face specific obstacles to obtain justice. In particular, national laws often fail to recognise rape and other forms of CRSV against males and/or criminalise same-sex relations.[2]

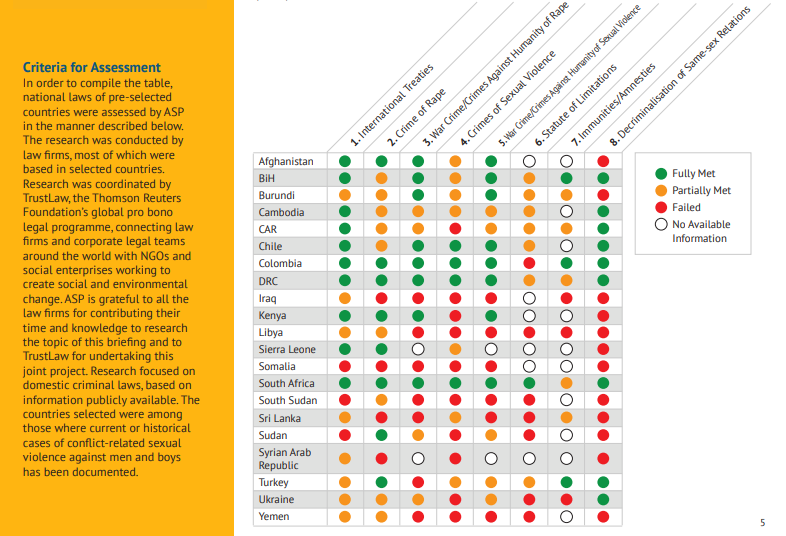

Partnering with law firms around the world (under the auspices of TrustLaw),[3] All Survivors Project (ASP) conducted an analysis of national legislation of twenty-one countries in situations of conflict or post-conflict and political violence, identifying best practices and shortcomings in the criminalisation of CRSV against men and boys. [4]

Our findings paint a worrying picture with many countries continuing to fall short of their obligations and commitments to criminalise all forms of CRSV.[5]

In thirteen of the twenty-one countries reviewed, laws fail to proscribe rape against men and boys, or do so in ways that fall short of international standards, denying survivors legal protections and contributing to impunity for these grave violations.[6] Lack of recognition in law can also inform broader social attitudes in which male victims/survivors are not acknowledged and the stigma surrounding sexual violence against males is exacerbated.

In addition, national legislations in ten countries fail to effectively criminalise other forms of sexual violence such as enforced sterilisation, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, genital violence and sexual mutilation, forced nudity and other acts which constitute sexual humiliation.[7] In another seven countries, other shortcomings of national law related to the criminalisation of CRSV have been noted.[8]

Only eight out of twenty-one countries explicitly include rape and other forms of sexual violence as war crimes and crimes against humanity.[9]

Another significant obstacle to justice for male survivors of CRSV is the criminalisation of samesex relations, despite clear obligations under international human rights law to decriminalise it. Our research shows that twelve out of the twenty-one countries reviewed continue to criminalise consensual same-sex relations.[10] In countries where same-sex relations are criminalised, legislation prohibits specific sexual acts such as ‘sodomy’.[11] In other countries, prohibited acts can include ‘acts against nature’, ‘indecency’ or other vague terms which place broad discretionary powers in the hands of law enforcement agencies and prosecuting authorities allowing for illegal intimidation, harassment and arrest of people suspected of engaging in consensual same-sex relations.[12] Most laws criminalising same-sex relations apply to all genders, but some apply only to men or only to women.[13] Criminalisation of consensual same-sex conduct violates the right to privacy and the right to non-discrimination under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[14]

Such laws, in addition to being discriminatory, can tacitly encourage violence and can deter survivors of sexual violence from seeking justice or medical and other support for fear of being arrested and prosecuted, as noted, for example, by the Secretary-General in the context of South Sudan, where “male survivors fear being classified as homosexuals and liable to prosecution under section 248 of the Code, which criminalises ‘carnal intercourse against the order of nature’”.[15]

ASP and TrustLaw research also points to examples of good practice which proves that with political will and support from the international community, member states can reform their laws to offer better protection for all persons against sexual violence.

The Penal Code of Afghanistan, which entered into force on 14 February 2018, defines rape in a genderinclusive manner and recognises rape and other forms of sexual violence as a war crime and as crimes against humanity.[16] Colombia’s Criminal Code includes crimes of sexual violence specifically in the context of armed conflict, including rape, forced nudity, forced prostitution, sexual slavery, and trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation.[17] The Criminal Code in Turkey, amended in 2014, criminalises sexual assault, defining it as violations of ‘the bodily integrity of another through any sexual act’.[18]

ASP believes that comprehensive national laws are necessary but may not be sufficient to deliver justice for all survivors of CRSV. Enactment of strong legislation needs to be accompanied by consistent and effective investigation and prosecution of crimes of sexual violence in armed conflict. In this regard, some effective prosecutions have been achieved at the international level and by hybrid courts.[19] Further, the application of universal jurisdiction can offer an important venue for criminal accountability, as the current trial in a German court of suspected former Syrian intelligence officials charged with crimes under international law, including sexual violence, demonstrate.[20]

However, at the national level justice continues to elude the vast majority of victims/survivors of sexual violence in armed conflict, and prosecution of cases involving men and boys remains rare. The report of the Secretary-General on conflict-related sexual violence offers a grim picture in relation to criminal accountability for CRSV with very few examples of investigation and trials by national authorities.[21] Further, ASP’s research suggests that even in countries with adequate legislation, national criminal justice systems often lack awareness, specialised expertise, resources and political will to investigate and prosecute CRSV against men and boys.[22]

Key Recommendations

In April 2019, UN Security Council resolution 2467 urged “Member States to protect victims who are men and boys through the strengthening of policies that offer appropriate responses to male survivors and challenge cultural assumptions about male invulnerability to such violence.”[23] The Report of the Secretary-General on conflict-related sexual violence notes how “strengthening the capacity of national rule of law institutions is critical in order to advance credible and inclusive accountability processes for past crimes, as well as for prevention and deterrence of future crimes.”.[24]

ASP supports this analysis and encourages the UN Security Council and all UN Member States to consider adopting measures and advocating on steps needed to ensure accountability for CRSV for all persons, including men and boys.

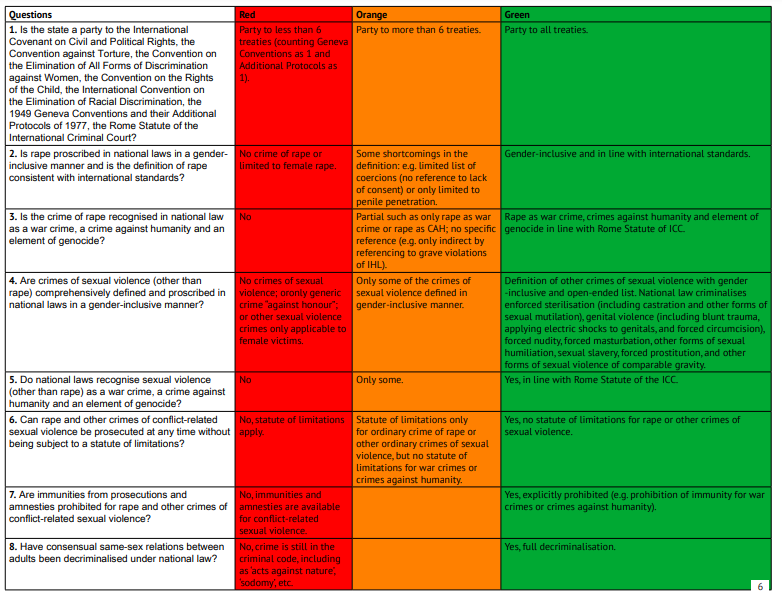

ASP recommends that Member States review and amend their criminal laws to ensure that:

- Rape is criminalised in a gender-inclusive manner and is defined in ways consistent with international standards and best practices;

- Crimes of sexual violence (other than rape) are proscribed in a gender-inclusive manner and include, but are not limited to, enforced sterilisation (including castration and other forms of sexual mutilation), genital violence (including blunt trauma, applying electric shocks to genitals, and forced circumcision), forced nudity, forced masturbation, other forms of sexual humiliation, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, and other forms of sexual violence of comparable gravity;

- Rape and other crimes of sexual violence are recognised as war crimes, crimes against humanity and as an element of genocide, in accordance with international law;

- Consensual same-sex relations between adults is decriminalised in law and in practice.

ASP also recommends that the UN Security Council strengthens its existing recommendations to:

- Urge Member States to improve legislation to foster accountability for sexual violence, including through ensuring that national penal legislation proscribes rape and other forms of sexual violence in a gender-inclusive manner and consistently with international standards;

- Request the Secretary-General and relevant United Nations entities including the Team of Experts on Rule of Law and Sexual Violence in Conflict to continue to support national authorities in justice reform initiatives to strengthen the investigation and prosecution of sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict situations and to ensure that national penal legislation proscribes rape and other forms of sexual violence in a gender-inclusive manner and consistently with international standards.

All Survivors Project/TrustLaw

Overall table of legislation on rape and other crimes of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) in selected states

References[+]

| 1↑ | Report of the UN Secretary-General on conflict-related sexual violence, UN Doc. S/2020/487, para 13. |

|---|---|

| 2↑ | See, for example, Ingrid Elliott, Coleen Kivlahan and Yahya Rahhal, “Bridging the Gap Between the Reality of Male Sexual Violence and Access to Justice and Accountability”, Journal of International Criminal Justice 18, 2020, 469–498. |

| 3↑ | TrustLaw is the Thomson Reuters Foundation’s global pro bono legal programme, connecting law firms and corporate legal teams around the world with NGOs and social enterprises working to create social and environmental change. ASP wishes to thank all the law firms which contributed their time and knowledge to research the topic of this briefing. |

| 4↑ | National laws of the following countries were reviewed: Afghanistan, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Burundi, Cambodia, Central African Republic, Chile, Colombia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Kenya Libya, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, Turkey, Ukraine, and Yemen. These countries were chosen because of documentation of on-going or past cases of CRSV against men and boys. |

| 5↑ | See page 5 for a table summarising the findings. ASP is planning to publish a full report with details of legislation for each country examined. |

| 6↑ | Bosnia & Herzegovina, Burundi, Cambodia, Central African Republic, Chile, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, the Syrian Arab Republic, Ukraine, and Yemen. |

| 7↑ | Central African Republic, Iraq, Kenya Libya, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, Ukraine, and Yemen. |

| 8↑ | Afghanistan, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Burundi, Cambodia, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, and Turkey. |

| 9↑ | Countries that include rape and other crimes of sexual violence as war crimes and crimes against humanity are: Afghanistan, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Burundi, Chile, Colombia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya and South Africa. |

| 10↑ | Afghanistan, Burundi, Iraq, Kenya, Libya, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, and Yemen. |

| 11↑ | For example, Article 646 of the Penal Code of Afghanistan. |

| 12↑ | For example, Article 162 of Kenya’s Penal Code criminalises ‘carnal knowledge of any person against the order of nature’ while the Penal Code of Sri Lanka criminalises as ‘unnatural offences’ the ‘carnal intercourse against the order of nature’ (sections 365) and ‘gross indecency between persons’ (section 365A). |

| 13↑ | For latest trends and developments on laws related to same-sex relations, see International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA), State-Sponsored Homophobia, 2019, https://ilga.org/state-sponsored-homophobia-report. |

| 14↑ | In 1994 the Human Rights Committee held that a provision of a Tasmanian law criminalising consensual sex between adult males which “enabled the police to enter the household” where “two consenting adult homosexual men may be committing an offence” violated Article 17 of the ICCPR, Toonen v. Australia, Communication No. 488/1992, UN Doc. CCPR/C/50/D/488/1992 (1994). Toonen has subsequently been uniformly followed by UN human rights bodies. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has unequivocally stated that “States that criminalize consensual homosexual acts are in breach of international human rights law since these laws, by their mere existence, violate the rights to privacy and non-discrimination”. See Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Discrimination and violence against individuals based on their sexual orientation and gender identity, UN Doc. A/HRC/29/23 (2015). |

| 15↑ | Report of the UN Secretary-General on conflict-related sexual violence, UN Doc. S/2020/487, para 47. |

| 16↑ | Article 636 defines rape as: “A person who has sexual intercourse with another person or penetrates body parts or any other object in vagina or anus of the victim using the following means: force, threat, other intimidating means; taking advantage of physical or mental disability of victim, or disability of the victim to express consent, including male or female, or by feeding sedative drugs or other substances that alters state of consciousness shall be deemed perpetrator of rape. |

| 17↑ | Colombia Criminal Code, 2000, Articles 138 to 141. |

| 18↑ | Turkish Criminal Code, Law No. 5237, 2004, Article 102(1) (as updated 2014). |

| 19↑ | The conviction by the ICC in July 2019 of Bosco Ntaganda, the former leader of the Union of Congolese Patriots/Patriotic Forces for the Liberation of Congo, as an indirect co-perpetrator of rape committed in the DRC in 2002-2003 as a crime against humanity and as a war crime, was the ICC’s first conviction for sexual violence and a rare case that characterises CRSV against males as rape. The case is also important for holding an accused, who was a superior, liable as an indirect perpetrator of CRSV. See Prosecutor v. Bosco Ntaganda, (ICC-01/04-02/06), Judgment (8 July 2019) 321- 323, 623, 940-942, 1199 and Part VII. |

| 20↑ | As noted in the report of UN Secretary-General on conflict-related sexual violence, “the German federal public prosecutor indicted and arrested a former Syrian official, Anwar R., affiliated with the Syrian General Intelligence Service’s Division 251, for more than 4,000 counts of torture as a crime against humanity, including rape and aggravated sexual assault.” (Report of the UN SecretaryGeneral on conflict-related sexual violence, UN Doc. S/2020/487, para 58). For more details see also Human Rights Watch, “Germany: Syria Torture Trial Opens.” 23 April 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/23/germany-syria-torture-trial-opens. |

| 21↑ | The Report of the UN Secretary-General on conflict-related sexual violence identifies some examples of limited progress at national level, including in Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, South Sudan (see Report of the UN Secretary-General on conflict-related sexual violence, UN Doc. S/2020/487). |

| 22↑ | See All Survivors Project, Checklist on preventing and addressing conflict-related sexual violence against men and boys, December 2019. |

| 23↑ | UN Security Council resolution 2467 (2019). |

| 24↑ | Report of the UN Secretary-General on conflict-related sexual violence, UN Doc. S/2020/487, para 7. |